You can listen to, read, or download this interview in several different ways…

To listen to this conversation you could press play on the embedded audio player below, but then you might miss out on future episodes, wouldn’t you?

Click Play Below to Listen to My Conversation with Roy Dean…

So the best thing to do is to subscribe to The Strenuous Life Podcast using the podcast player that you almost certainly already have on your phone!

(For example, if you have an iPhone then it’s the purple app with the antenna-like thing in it. Just click the Apple Podcasts link below and it should open up that app for you.)

Here are the links to find the podcast on various players (This one is episode 13)…

- Apple Podcasts (the purple app on your iPhone)

- Google Podcasts (the new google podcast app)

- Spotify (it’s free)

- Stitcher,

- Soundcloud,

- Google Play

Roy Dean Interview Transcript

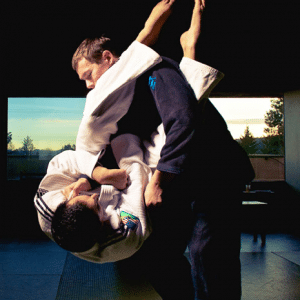

Stephan: Hey everybody. Stephan Kesting from Grapplearts.com here. Today, I’m going to be talking to Roy Dean. If you’ve been online, then you’ve probably run into his material on YouTube or his website. He’s a Brazilian Jiu-jitsu black belt with a really slick style on the ground and a very personable, very friendly teaching style.

But first of all, Roy just got back from England and I didn’t even get to find out why he was going to England. So what were you doing in England?

Roy: Hey, it’s good to be here, Stephan. I was in England visiting a couple of my affiliate schools out there and happy to say that they’re progressing very nicely. I awarded another purple belt when I was out there and the trip couldn’t have been better. Great people, weather was fantastic. And so I’m happy to be back in the States, but I look forward to those trips overseas to visit my friends and affiliates.

Stephan: I’ve always wanted to go to England. Did you get any time for sightseeing? Did you get those necessary photos with the Buckingham Palace guards or was it all work?

Roy: On my first trip to England, I did do that. We did kind of an exhaustive tour of London and Stonehenge and did all those goodies, but this trip was much more relaxing. I stayed with my friends, Steve and Kirstie. They have a place right on the beach in Sandbanks. And since the weather was fantastic, there were a number of people on the beach all the time. It was work but they also combined it into a vacation and so it was really excellent.

Stephan: Cool. Well, let’s get sort of started. For the people who have never met you or don’t know anything about you, why don’t you take us a little bit through your martial arts history? I know you didn’t start in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. You started with the more traditional martial arts, as did I.

So I’m always interested to see what a person’s progression was, and why they decided that that rolling around on the ground with men wearing pajamas was a good idea…

Roy: It was definitely a progression. When I was 16, I was sent to Japan as a Rotary exchange student. And while I was over there, they asked me to do a Japanese art after school. I had a couple of different choices. I could do Kyudo, which is archery, Ikebana, which is flower arranging, but I chose Judo. They warned me, “oh, Judo training is very severe,” but I was ready for it. I wanted to work out my energy.

So I started training with my high school Judo team, which is similar to an American high school wrestling team. And I trained 6 days a week, competed once a month and really immersed myself in it. By the time I came back to the States, I had won enough competitions to receive my first-degree black belt, and then I just kept on going.

Judo in the U. S. is quite a bit different than it is in Japan. There it’s a cultural institution. It’s everywhere. Here, the level wasn’t the same. Training wasn’t the same. So I started to look elsewhere and ended up in Aikido.

I did Aikido for a number of years, then decided to get serious about it and moved into the dojo of an Aikido and Japanese Jujutsu master, named Julio Toribio. Sensei Toribio was in Monterey, California. So I moved from my hometown of Anchorage, Alaska to Monterey, California, lived in the dojo for 18 months, trained every class everyday and studied Japanese Jujutsu, Iaido, and continued to train.

During that time when I was actually living in the dojo, a friend introduced me to Claudio Franca, who was one of the first Brazilians in Northern California with a legitimate black belt in BJJ. So I began training with him and eventually received my blue belt under him.

By the time I moved to Southern California, San Diego, to continue my university education, and I got hooked up with Roy Harris. He was recommended to me by Garth Taylor, one of Claudio’s top students, for having a kind of intellectual approach, being that he came from a JKD background and he was one of the first Americans to get his black belt in BJJ.

Stephan: He’s a very, very serious student of the martial arts.

Roy: Oh, indeed. It’s difficult, unless you meet him, to really understand like how analytical his mind is and how deeply he studies things. And so he was the right teacher for me. At that time, I needed just a different, perhaps slightly more verbal approach and specifics on how to improve. I was a pretty good blue belt, and wanted to get to that next level of purple and continue my journey. So, he was the right teacher for me and purple through black belt, he awarded me those ranks. I’m very proud to be a student of his and to have him as my instructor and friend.

Stephan: When the student is ready, the teacher will appear, or the teacher who is right for the student at that time will appear.

Roy: It worked out in this case and hopefully it works out in other people’s cases as well.

Stephan: Alright. People always talk about how wrestling is a great basis for things like MMA. Even if you end up being more of a striking-oriented MMA guy, then the background of wrestling gives you that mental toughness. So do you think there’s a similar carry-over from Judo into Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, and/or Judo into submission grappling? What’s the relationship between those 2 arts?

Roy: That’s an excellent question. There is definitely carry-over between Judo and BJJ. If you start out in Judo, and if you can then empty your cup and be very receptive to the approach of BJJ, you’re going to come out ahead. I mean, just the emphasis on Osaekomi or immobilizations; being able to hold down your partner. Or the speed that is necessary in Judo. Or the sheer number of repetitions that you have to do in order to ingrain a throw in your muscular memory.

Sometimes on the ground, guys will be like, “yeah, I did the arm bar like 4 times each side, let’s move on to the next thing.” Judo teaches you early on that when it comes to repetition, you need more like like 400 times each side…

Stephan (interrupting): Per training session!

Roy: … Yes, 400 times per training session. You want to get to that point where a technique is like a reaction. It’s without thought.

I don’t have that much experience in wrestling. As a brown belt I did attend a wrestling camp, Mark Munoz and Urijah Faber were the coaches there, and it was very, very instructive for me to understand the wrestling mentality and it’s different.

A lot of wrestlers want to be as good as they can, as quick as they can, so they may not like the Gi. They only want to do submission wrestling. They just want to maintain top position and they feel that that’s winning. But on the other hand, because of the wrestling, they understand takedowns better, they understand repetitions, they understand being aggressive and how small those windows of opportunity can be if you set someone up for a shot. Plus the ability to generate pressure from up top, which wrestlers are excellent at. So having that background is a huge advantage. That puts them further ahead.

Obviously the rules of the sport dictate the training approach, and even the strategy for a match. Things are really compressed in Judo. Things are even more compressed in wrestling, but they’re both valuable arts and I don’t really see that much difference between BJJ, Judo and wrestling. To me, they’re all grappling arts and, in a way, they’re all arts of angles, distraction and leverage, which I feel is jiu-jitsu.

Stephan: There’s a universal language of movement. But certainly the rules do tend to influence the way in which the art is expressed, or the ways in which the angles and the leverage and the universal principles are expressed.

My own main instructor for Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Marcus Soares, always said that if you want to know if your pin escapes work, go against a Judo guy because their pins are fierce. Their pins a lot tighter than a lot of jiu jitsu guys because they’re not going for submissions as much. If I’m going against a Judo guy in a Judo competition and he pins me for 25 seconds, then the match is over. He wins. So why would he even bother going for an arm bar or a triangle or a choke. He’s just going to go for the pin. That’s why Judo has this dogged clamp and hold mentality. Even if there’s an earthquake and the ceiling falls down, they’re going to hold on to that pin.

Roy: Exactly, and they can afford to put 100% energy in that direction for the pin.

And similar with wrestling. I found during the wrestling camp that it’s remarkably difficult to actually pin someone just on the shoulders. Not just put them on their back, but actually pin their shoulders, especially when they’re savvy with a strong bridge. So, they can afford to put 100% energy in that particular direction. And BJJ guys just won’t do that. The pin is not the end. So it’s different…

Stephan: It’s not flowing with the go…

Roy: As Rickson beautifully stated.

Stephan: Well, we’ve talked about Judo, we’ve talked about wrestling. You mentioned another martial art that’s typically not thought of as very combative, and that’s Aikido.

I once heard Aikido described as an excellent art of restraining aging professors run amok. But I’ve seen you use certain Aikido techniques, and seen you teach some Aikido techniques. And I have also incorporated a few of them into my grappling, so why don’t we talk about how Aikido, and art which is usually trained cooperatively, translates into our art of grappling and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, both of which are mostly competitively.

Can you talk a bit about what you learned from Aikido which you then use on the mat in jiu-jitsu?

Roy: There are so many lessons in Aikido that I’ve been able to translate over to jiu jitsu of all kinds, and BJJ. The thing with Aikido is it is generally considered a cooperative martial art, a non-violent, purely defensive, cooperative martial art.

Now when you have been exposed to a variety of Aikido styles (and even some Japanese Jujutsu styles that many people would label as ‘Aikido’), and the further you go back to the roots of Aikido, then it becomes more hard style. They start using pressure points, they might have strikes, the circles are tighter.

But the lessons of Aikido, is that it’s all about being okay to blend. And you don’t see blending much, with wrestling or Judo. Well, they kind of talk about blending at the higher levels of Judo… But in Aikido, it’s stressed from day one. It’s all about being able to blend with the attack. Being able to time the attack.

If somebody gives you 7 units of energy and you only have 3 to oppose it with, they’re going to win. But then if somebody gives you 7 units of energy and you blend with it and add your own 2, then you have 9 units of energy going in your direction and voila, you magnify your strength. But that takes a lot of skill.

With Aikido, I think the emphasis on blending with the attack and being able to see distances very, very clearly, make it more like striking than grappling.

When someone comes in with a strike you have to be able to corkscrew your hips in order to generate power, you drop your hips and corkscrew your hips.

And if you’re doing BJJ, you’re doing the same thing but you’re doing it in the opposite direction. When you are on your back and you shoot your hips up and corkscrew for an arm lock, that’s the same motion. It’s just, in Aikido, if you’re doing a wristlock, you corkscrew your hips down. In BJJ, you corkscrew your hips up.

So, it helps to understand body mechanics. It gives you the green light to go ahead and blend with your partner. In my own particular BJJ style, there’s a lot of blending. I can sort of enforce my will and generate a lot of pressure, but generally, if somebody’s stronger, I just recognize, “oh man, that guy’s stronger,” and I’ll try to blend with it as much as possible.

So Aikido, like all martial arts, goes in and out of popularity. But it’s powerful. And if you get together with a really good practitioner of Aikido, it can be impressive and it’s not to be underestimated. That’s the first rule of being a martial artist. Respect everyone. Don’t underestimate anybody because that can be a bad day for you.

Stephan: I remember sparring with a guy, many years ago, who had done a lot of both Aiki Jitsu and Aikido. And he wasn’t a frail wisp of a man; he was a big powerful guy. You always had to be careful sparring with him, regardless of whether you were standing or on the ground, because he always would try to get some kind of forearm-on-forearm contact. He would try to step forward, get a point of reference and from there, he would go for the wristlock 100% of the time. This is my story, so in my version of the story he never got me in a wristlock but he came very, very close many times. I’d be super-worried about it all the time, whether we were standing or on the ground. So there is, I think, some carry-over from the technique itself. Certainly I adopted a few of the wristlocks from Aikido or Aiki Jitsu, and I know you have as well…

Roy: The wristlock is a great technique to carry-over. You can apply it standing. And it’s even better on the ground because you’ve eliminated all the movement options. Let’s say that somebody almost gets you in a wristlock when you’re standing; you have a chance to get out of it by moving to the third point or wherever they’re trying to throw you. But on the ground, if you pass the guard and have someone in side control, your shin might be over their bicep, and now you use your hand to press down on their wrist, their elbow is backstopped against the ground. They can’t move. They are done.

So they can be really effective and very sneaky. Because the range of motion is so small, they can come on very quickly. And so they are definitely effective attacks.

But if, you know, you need a lot of tricks in your bag. If you are only relying on your wristlocks and you don’t have other techniques to to set it up, then if you miss it, it’s not a good day.

I think that Aikido could definitely benefit from incorporating a little more resistance in their training method. Their argument says that it can’t be done, but when I first encountered BJJ, I was like “there’s no way guys can do this without getting injured.” But of course it IS possible. Every once in a while, you get a little tweak, but you can do more than you think with resistance and learn quite a bit. I think Aikido could definitely use a little bit of Kano’s innovation of randori.

Stephan: Do you know if randori was part of the original Aikido? Because in the limited amounts of reading I’ve done about the early history of Aikido, it seems like the founder of Aikido and the people around him were pretty badass.

Roy: Oh, Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, was definitely, a badass. He had razor-sharp technique. But just because somebody was badass back then doesn’t mean that the art they hand down is necessarily badass. Each practitioner, every generation has to reinvent effectiveness for themselves.

When I was studying Aikido, I was like “okay, this is good. It’s not quite working for me yet. I don’t have the ability that O-Sensei had. Maybe I should be studying what he studied rather than studying the art that he handed down.” It’s a different way of thinking about it.

One thing that he did want, he studied Daito Ryu Aiki Jujutsu, he didn’t study Aikido, so that’s part of it. And in learning other Japanese Jujutsu forms, like Hakkoryu Jujutsu or Seibukan Jujutsu, I was able to study techniques that he had actually eliminated out of Aikido, techniques he had taken out. So you look at Aikido a little bit differently and said, okay, he knew these techniques but he chose not to teach them or they weren’t part of his personal expression.

Also, he had a lot of attributes. They said his arms when he worked in Hokkaido for some time to kind of found a town out there, and he was doing quite a bit of logging. Apparently, his arms were massive. Massive, like as big as people’s legs. So he was a strong guy. He trained like a madman. And some people, there’s a little bit of speculation that there may have been some bipolarity there, but he trained like a madman. He had all the physical attributes and he had razor-sharp technique taught by a guy who was a true killer, Sokaku Takeda, who had killed many men in his time. So, you combine all that, yeah, you’re going to end up with somebody who’s effective.

And particularly against Judo players at that time, when you read stories about the Judo guys challenging Morihei Ueshiba, the Judo guys, like Kenji Tomiki, when he went and attacked him, he was like, “This old man, I’m not going to attack this old man.” [Ueshiba] said “No, go ahead and attack me.” So when Kenji Tomiki attacked him, he found himself thrown to the other end of the room. And he was like, “Wait a minute. Alright, let me do that again.” He’s like, “Okay, you can do it again.” So [Tomiki] attacked him again with everything he had and he mysteriously found himself thrown to the other side of the room. Then he bowed and said I would humbly like to become your student.

And so what was that? Well, a lot of it is technological superiority. I’m not saying the techniques of Aikido are superior to those of Judo. I’m saying that he was using a technology, basically a form of standing grappling. As soon as somebody goes in to reach for you, you blend with it. In Judo, you just grab each other and then you begin. But because he was working at a different range of motion, but really no different than Royce Gracie in the first couple UFCs. Because he was working in that altered range of combat that the Judo guy wasn’t familiar with, he had, clearly, the upper hand.

So, I think that goes a long way in explaining a lot of the stories of Aikido being able to best Judo in a few challenge matches in the early days of the art.

Stephan: I like what you were saying about that every practitioner or every generation has to reinvent the art for itself. If you take, arguably, the most effective striking system, let’s just say it’s boxing. It could be Muay Thai, it could be something else. Let’s just say it’s boxing and I decide to get rid of sparring in boxing and we’re all just going to make it drills. And then I teach a whole generation of students, and then they go and teach it to a whole generation of students. Within a couple generations of students, we’ve taken it from, arguably, the most effective striking art to something that resembles, it’s going to end up resembling one person’s solo forms of Kung Fu, where you’re hopping around and pretending to bob and weave, and you’ll have gotten rid of most of the combat efficacy within a couple of generations.

So it would be up to each subsequent generation to check in and ask, “wait a second, are we still doing this in a way that will work?” Typically, in our world, that would be using it against resistance. We are really trying to arm bar somebody who’s really trying not to get arm barred and is really trying to arm bar us in return or choke us out or whatever.

Roy: Exactly. That’s a perfect way of expressing, unfortunately, what’s happened in some arts. And that’s why I love competition. I love the ability to compete. You can compete, you can not compete, but having the option of competition with that full resistance is what keeps the teeth sharp in an art.

Stephan: Obviously, every time you step on the mat and spar with somebody, it’s a form of competition but let’s talk about the big picture, like the official version of competition where you’re going to a tournament. How much of that have you done?

Roy: I’ve done a fair amount. I competed every month in Japan doing Judo competitions. When I was a blue belt, I competed quite a bit. The competition scene was much smaller in those days. It was mainly Northern California, where I was training, so United Gracie tournaments and the US Open, Claudio Franca’s tournament. And then when I moved to Southern California, blue belt, purple belt, I continued to compete.

And competition, for me, was part of the process. I wanted to see what I could do. I wanted to go out there and I wanted to improve and I knew the competition. The best guys were competing. The guys I admired were competing and I want to be like them. I wanted those skills. I want to be able to go out in competition and represent. And I lost every match until I won my first competition, which was Grapplers Quest. It was great. I wouldn’t trade any of those competition experiences for anything.

If my students want to compete, I, first of all, pick a good competition for them to do because not all competitions are the same. And I try to facilitate a good experience for that.

I’m not competing anymore. I don’t feel the fire that I used to. And honestly, if you’re not really fired up about a competition, if you’re not incredibly motivated to go out there and win, then, at high levels, you shouldn’t be out there because guys are hungry. They’re very, very hungry to win, and if the fire isn’t in the belly anymore, there are other challenges in life where you can invest your energy.

But the competition experiences that I did partake in were fantastic and I was happy I was able to win some competitions and just to be able to pass that on to my students, if they choose to go in that direction.

Stephan: What was it for you that made the jump? It’s not like you lost, you lost, you lost, you lost, then you won a whole bunch. So what was the quantum leap? Or what was the shift that happened for you? Or was it just luck and time in the art?

Roy: It was a combination of factors. Number one, I was tired of losing and I had said “This is it.” I remember warming up for that Grapplers Quest and I was like, “This is it. This is my time. It’s going to happen now.“ And there are, yeah, it was great. I had also begun the shift to more drilling, instead of just showing up to class and rolling. So, I had gotten a training partner at that time at blue belt. One of my best friends, Brad Hirakawa, we became training partners. We started drilling under Mr. Harris’ guidance. It was like, “Okay, you’ve got to get a training partner and you have to start drilling.” So doing basic drills… I’m going to try to do arm lock or foot lock drills or just drilling.

Stephan: You mean competitive drilling or technique repetition drilling?

Roy: We did technique repetition drilling but making sure that every rep was done with with authority and just engraining those things into my body. That is when I really turned the corner. You turn a corner when you go from white belt to blue belt, but then to get to that high blue stage where you’re on the bridge between blue and purple, that is all about being able to do enough repetitions so that you understand and can flow effortlessly from one technique to another within particular systems of techniques, like Omo Plata, Triangle, Armlock, or those related techniques you can flow very smoothly through with no gap in between them.

So I had undertaken that kind of training. So it’s a little bit of mental focus, determination. Also It was a no gi tournament. I tend to do better no gi. My weight was on.

I feel, a lot of times, no matter how hard you train, competition success is often a combination of factors. You choose the right weight category. You’re paired up with the right people. Your draw in the tournament is favorable. You’re well rested. Your training camp was great. You have relatively low injuries or maybe you have an injury that makes you focus that much more. You had a hard weight cut you suffered for and you’re mentally that much more focused than you’ve ever been before because you know how much you’ve put into this particular experience.

Competition is a beautiful thing and for a lot of people, it’s their rite of passage. But competitions are not always great for people in that the likelihood of injuries is much higher. Sometimes they train, train, train, they pay a lot of money, they’re out there for like 3 or 4 minutes, they lose. Maybe they had a bad experience. Maybe it was a bad referee call. I mean these things happen. So I feel like true competition success is a combination of factors that all align and then voila, it just happens one day. You’re at the podium and you’re smiling and then you celebrate that night.

Stephan: If you had to guess what you think per minute of rolling or per hour of rolling in competition versus in class, what do you think the injury rate differential is? How much more likely are you to get injured in one hour rolling in a competitive setting versus one hour of rolling in a more friendly class setting? I ask because I remember reading what the statistics were in amateur wrestling. I have no idea what the statistics are in jiu-jitsu and MMA, where you have submissions allowed and, well, in MMA, you can punch people. But what do you think that the number is?

Roy: Not to cheat the question, because I think I may have seen you post that. I would suspect it depends on the competition, it depends on the rules. Like for example, with just your local tournament, white belt, it’s probably like maybe 2 or 3 times higher that you’re likely to get injured in a competition. And honestly, you may not even feel the injury in the competition because you’re so adrenalized, you’re so amped up.

But I will say that in preparation for competition, your intensity goes up quite a bit because you feel, “man, I’m going to be on the line.” And I’ve seen the shift. I’ve had the shift in me. I’ve even had my students call me out when I didn’t let them know I was going to compete but they’re like, “Why are you being so mean? What’s the matter with you? Why are you being so short with people?”

Things shift when you compete. The intensity of your training gets escalated. And so your likelihood to get injured while preparing for the competition is definitely higher. Your risk of injury in the competition I think is higher.

So those, I think, are both contributing factors. But tell me about the wrestling statistic.

Stephan: Oh, if I can, if I recall correctly, then I think it’s 40 times more likely per minute of competing versus per minute of training. That’s a very explosive art, but on the other hand, we have joint locks and certainly, if you and I were competing and you had me in an arm lock then I would try and fight out of it for a lot longer than I would if we were just rolling around for fun. And you would probably hold it and apply it just a little bit harder than you would if we were just rolling around for fun. And then you get the leg locks. If you’re sparring at all with heel locks and stuff, then I often just get to the position and don’t even apply it when I’m sparring. But if I was competing, I would apply it if it was legal.

Roy: Absolutely. I remember seeing the Abu Dhabi competition in New Jersey and I was amazed because of heel hooks and toeholds. So many guys limped off the mat and I just realized that was another, I was like wow. I just can’t believe how much these guys want it and how unwilling they are to tap to a submission. At that level, you have to ask yourself are you willing to sustain an injury. And these guys, of course they don’t want to be injured, but sometimes, too much heart can lead to that, and I’ve seen it many, many a time.

Stephan: Or the Jacare/Roger Gracie match, where Roger caught the full-on arm bar and took Jacare, I’m trying to remember, about 15 seconds to work his way out of it, and then his arm was completely useless for the remaining 25 seconds of the match. And that’s another example of heart or a serious level of heart and determination to win.

Roy: Oh yeah.

Stephan: If you don’t have that level of determination then maybe you shouldn’t be doing it.

Roy: That’s true. And just as an aside, sometimes, I’ve been injured many times in my career, even just rolling. And I just try to take those opportunities to continue rolling, unless it’s something really, really bad. I try to take those opportunities to continue rolling so I can say, okay, I’m injured, I tore my MCL, I just broke my hand, but to continue rolling. As an instructor at my level, I think that can be beneficial training. That’s not for everyone, but that’s a different thing. There are different levels of training that you can undergo. I know some BJJ instructors have put their teachers through actual physical pain tests. It’s not just heart. It’s like it’s straight-up pain. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that if people understand what they’re getting into. But that’s not for the recreational player. That’s for building a different level of mental fortitude.

Stephan: Every once in a while, you see a conversation online in one of the forums and their question is basically some variation of should you be allowed to get your Brazilian Jiu-jitsu black belt if you’ve never competed. Is having competed a necessary prerequisite of, whether you won or lost, of getting the black belt? What do you think about that?

Roy: Is it an art or a sport? I feel it’s an art that has a sport component, a Vale Tudo component, and a lifestyle component. So you do not, in my opinion, you don’t have to compete in order to get a high level of technical mastery. Sure, it puts you under duress in a very different way. And if you want to have that experience, that’s great. I think you’ll be stronger for it. But do you have to in order to get your black belt? No. Do you have to get in a fight to know that BJJ is effective? No.

I’ve never been in a fight in my life. A couple of close calls, but I’ve never been in a fight and I have no intention of getting in one. Do I need to get in a fight? I don’t think so. And competition matches are limited rules fights. I mean combative sports are limited rules fights.

And BJJ, to me, is an art and it’s something that’s much bigger than the sport. The sport, because it’s, I’m happy that it has gained a popularity, but jiu jitsu is a flexible and yielding art that can suit many different approaches and many modes of practice.

So if you have been a lifer, you’ve been training for 15 years under very, very competent instruction, I don’t see any reason why you can’t get your black belt.

Stephan: So we agree, then, that you can’t become a world champion without having competed but you can become a black belt.

Roy: I agree.

Stephan: It’s like knowing you’re going to die in the morning focuses the mind wonderfully. Knowing you’re going to compete in a month sometimes focuses your training wonderfully, and Erik Paulson, I think it was, said that sometimes you learn more in a single competition than you do in 3, 4, 5, 6 months of training. And I think both of those things are true.

Roy: Oh, I agree.

Stephan: But it isn’t for everybody.

Roy: No, it’s not for everyone and not everybody wants to experience what you have to experience. There’s a roller coaster of emotions internally and externally. Emotions run high in competitions and I don’t think it serves everybody as well as some people make it out to be. So, it’s an option. It should always be an option. That’s what’s going to continue to keep the art strong.

But as you look at sport competition, the more sophisticated the entries into some of these submissions and some of these positions and as the positions get more exotic, it gets more and more removed from street defense. There’s nothing wrong with that. That’s the evolution of the sport aspect of the art. That’s great. That’s beautiful. Let’s keep that going. Let’s keep it going. Let’s explore the range of human movement and dynamic interactions and keep expanding the possibilities.

But the art is that powerful. It can incorporate all practitioners and all different styles.

Stephan: Oh no, somebody has jumped me in the parking lot. I’ll pull upside down guard.

Roy (laughing): Yes, exactly. That would be my first thought…

Stephan: Now, one thing that you’ve done, Roy, is that you’ve produced a series of videos. “The White Belt Bible”, “Blue Belt Requirements”, “Purple Belt Requirements”, “Brown Belt Requirements”, and obviously you’re working up to “Black Belt Requirements”. So, you’ve obviously given a lot of thought to what the belts mean. Could you, in sort of a condensed version, talk about how you see the progression from white to blue, blue to purple, purple to brown, brown to black and what that means and what you need to see in somebody?

Roy: Great question. I was just discussing this with my affiliate, Steve Greenaway.

White to blue is, it’s pretty cut and dry, in my opinion. White belt, you don’t know anything. You learn the basic movements. You learn defense. You learn basic attacks. I feel that a blue belt, a fresh blue belt should be able to, if attacked by someone that doesn’t know anything, they would be able to defend themselves. And that could mean they get pushed down, do a technical standup and run away. If they get pushed down, they do the proper ukemi, they can be protect their head, and round out their body. If they’re attacked, they may be able to do an arm lock from the guard or maybe even do a guillotine choke. So, against an untrained person, they would be able to submit them and be able to escape from that situation safely. I feel that is a great indication of what a blue belt is. And then I feel very comfortable giving somebody a blue belt if they have that level of skill.

Blue to purple: blue is a very thick belt. To get to purple in BJJ, you have to be able to string techniques together. And I often use the analogy of you learn words at blue belt, you learn letters and how to write the letters and, okay, what alphabet are we working on here at white belt. At blue belt, you’re learning words. At purple, you put those words into sentences and you start talking. And then, so somebody talking versus somebody that’s just learning their ABC’s, it’s not even fun. I mean it can be fun but it’s not that much of a challenge. Someone’s speaking sentences against somebody who knows a couple of words, it’s still, there’s no challenge, that’s the difference in levels. That’s why the purple belt is so powerful because they taste the essence of jiu-jitsu. They taste the power of jiu-jitsu when they’re able to have very small gaps in between one technique to the next.

Now, purple belt to brown belt, it’s more about adding conviction to your arguments. Yes, you can do triangle arm lock or whatever technique, but do you only play the guard? If you need to, can you play the top? You need to have a well-rounded game. And so if you’re more of guard player, to get to brown belt, I feel you need to work on your top game a lot, be able to generate pressure, be able to know when you’re in a good position and have patience, be able to hold your position when you’re passing the guard, not to freak out.

A lot of people at blue belt, they try passing the guard. They’re not quite successful. The guy defends, but they made progress and then people go back all the way to zero. They go all the way back to trying to pass the guard completely. Whereas a brown belt, there might be a difficult guard, he’ll just, he’ll pull half-guard. From the top, he will stuff a leg and hold his position there and work from that position…

Stephan: Like a ratchet…

Roy: He knows how to hold his ground and he’s got a lot of confidence. Conversely, if you have a strong top game, I want you to have a very playful bottom game and be able to submit people from the bottom.

So, purple to brown is a time of well-roundedness and also being able to have conviction in your arguments, be able to generate pressure from the top and the bottom, and then finally have multiple conversational threads. You’ve got to be able to stack your attacks. So, one thing doesn’t work, you go into the next thing. Blue to purple, you might have 2 things you’re working on. Brown belt, you have an array. You have like 5, 6 techniques that you can do. Depends on how they resist.

So, there are significant skill differences in between each belt level, I feel. And I think the ranking system in BJJ accurately reflects those different levels of skill.

Stephan: Now what do you think about the argument that although you can motivate people with belts, people will then mistake the belt for the end goal. They get so fixated on the belt that it disrupts their relationship with the art, it disrupts their relationship with their teacher, it disrupts their relationship with their friends and their training partners. They get all bitter, saying that, “well, I can beat Joe half the time and he’s a blue belt and I’m not. I’m going quit and go to another school because obviously my instructor hates me.” I’ve seen this so many times. It’s really frustrating for me when I watch this because it’s people whose initial joy at simply training is being corrupted by this focus on the belt.

Roy: I agree. I see it all the time myself. And it’s OK as as long as practitioner realize, “alright, I’m after the skill that the belt represents rather than the belt“, because there’s a whole slew of problems that stem from people getting the belt and then they’ve got to defend it. Some people think they want the responsibility and then they get it and they’re like, “Wow, I wasn’t really ready for this.” But under a competent instructor, he won’t promote you.

I mean students are different. Some students, they want the belt, they’re ready for it, you give it to them and they’re happy about it. Others refuse the belt, you have to give it to them and then they’re forced to step it up. And it has a lot to do with personality. But I think a really good instructor will be able to recognize the personality type, the learning style, what that person’s ready for, etc, etc.

Now, if people, if they don’t like that Joe got promoted, they’re like “he’s the same rank as me but I beat him up, and that kind of discredits my own rank”. People just need to drop that. There’s too much personal identity involved with that. You’ve got to go and you have to just say, hey, that’s what the instructor deems.

Sometimes the instructor looks at people differently. It’s not a uniform standard of skill. Sometimes, the instructor judges you based on “Could you beat yourself up from a year ago?” The day you walked in, if you faced yourself, would you be able to submit you. Kind of a strange question, but like that’s how far is your individual progress in the art. Let’s not compare it to all these other people. Sometimes that gets tricky. People are accelerating in their development. They’re getting better. You’re getting better. You get frustrated.

And the whole pecking order thing in BJJ is great but there’s quite a bit of cognitive dissonance when people aren’t settled with their position. People at the top, people that get disgruntled about their rank and where they are and when they should be promoted, that’s usually with people that are very, very close to them in skill. Whether they feel that, “Oh that guy muscles it” or whatever, they’re usually fairly close in skill. They don’t have problems with the people that are way better. The disgruntled blue belt is not complaining about the brown belt that whoops up on him, nor is he complaining about the 3-month white belt. No, he’s complaining about the guy who he’s basically neck and neck with and that’s where your frustrations are because you’re kind of vying for where you are in the pecking order. Some days you’re on top and some days you’re on bottom, but you should just be content with your overall position in the pecking order.

So if you can just be okay with that, look at the big picture, kind of step back, say, well, how do I fair against myself if I were to face the person I was 3 years ago when I walked into this school, I think that helps settle you. That helps ground you a little bit and helps prevent some of this short sightedness about rank when it’s really just being involved in the art is the joy itself, the people that you’re able to meet with a common interest. Don’t shortchange that because of a little ego squabble.

Stephan: That approach also gives some perspective to people who are thinking, “I’m just not getting any better. Joe could beat me up a month ago and Joe can still beat me up now or Joe could beat me up half a year ago.” Because the thing is that Joe’s been getting better the same time as you. So often, when new people start, they get really, really discouraged up until another new person starts. And then they realize how far they’ve come because, all of a sudden, they can kick somebody’s butt.

Roy: Exactly.

Stephan: And the rising tide lifting all boats is a great thing but it’s also confusing if you’re first exposure to a whole cohort of people getting better at the same time.

Now, you’ve produced DVDs, you’ve produced iPhone apps and you’ve produced some Android apps. Can you talk just a little bit how people can get a hold of those or see what you have to offer?

Roy: Absolutely. Early on, I entered the instructional DVD market and now I’ve entered the app market for iPhone and I do have some Android apps available. You can just go to roydeanacademy.com, explore my website, check it out. I have an app store there that links to iTunes. I also have instructional DVDs that you can order directly through me or they’re available on Amazon and other fine retailers. And soon, I’m going to be launching an online component where you can subscribe to the website and have access to any of he DVDs I’ve produced. And there’s other media that isn’t available on DVD, for example, I did a triangle choke seminar that’s available only on iTunes as an app.

And additionally, I’m going to start to film classes. Some will be public classes that I actually teach at my academy. Others will be a more one-on-one private lesson instructionals. But I’m looking forward to being able to offer that, particularly for my affiliate students. I want to them and my affiliated clubs, I want to get them closer to what the experience is here at the home academy and be able to show them. Although they’ve been here and trained with me, have them be able to take my lesson plans, be able to, if they want to mimic the lessons that I teach, that’s totally fine. I just want to be able to get them a little bit closer so they’re able to disseminate the techniques that much more accurately.

So, I’m excited about this next chapter. It should launch in the fall of 2012. I’m working with a few developers on this and it’s off to a good start. So I’m really excited about being able to offer that both to my affiliates, for which it will be a free service, and then for anyone that is interested in training but can’t actually make it to Bend, Oregon to join us at the main academy.

We love having visitors. We get them from all over the place. And a number of people have written me over the years saying do you have an online program, I would love it if you had an online program similar to what the Gracie’s do.

Personally, I’m not ready to, I’m not comfortable giving out rank online. That’s not something that I’m ready to do or comfortable doing. And each affiliate, I have to meet them face-to-face. We need to spend time together. I’m just very conservative in that aspect. However, I like having a transparent mode in my academy, and that’s what the whole YouTube phenomena that I involved myself with. I got involved with YouTube early on before YouTube was big and posting belt demonstrations. I just wanted people to see, hey, this is my process. And I won’t be teaching BJJ forever, but while I do have an academy, while I do have students here, I want to share my process, and hopefully that will inspire other people so they can do it too. They can have their own process. They can develop students to a higher level of skill and be able to empower those people to go out and tackle other challenges in their lives.

Stephan: And if people want to come train with you hands on, then they should travel to Bend, Oregon, where your school is.

Roy: Exactly. And people always love, they’re like, why are you in Bend, Oregon? And then they come out to Bend and they see what it’s like out here and it’s phenomenal. It’s beautiful town, clean air, beautiful river running through the town, parks and it’s an outdoorsman’s paradise. So if you’re interested in rock climbing, mountain biking, skiing, you name it, it’s a very fit town, very hip and it’s home. So, anyone that wants to come by, have a getaway and have a jiu jitsu adventure, you’re more than welcome to swing by. We love having visitors on the mat.

Stephan: So you found the perfect midway point between Alaska and Southern California. I’m happy for you.

Roy: Exactly. That’s exactly how I feel about it.

Stephan: Excellent. Well, thank you so much for meeting with us today and sharing your knowledge with the Grapplearts readership and listenership and I look forward to seeing what you’re up to in the future. Take care, Roy.

Roy: I appreciate it so much, Stephan. Take care

The post Podcast EP13: Roy Dean on BJJ, Aikido, Judo, Wrestling, and the Martial Artist’s Path appeared first on Grapplearts.