[First published in 2009.]

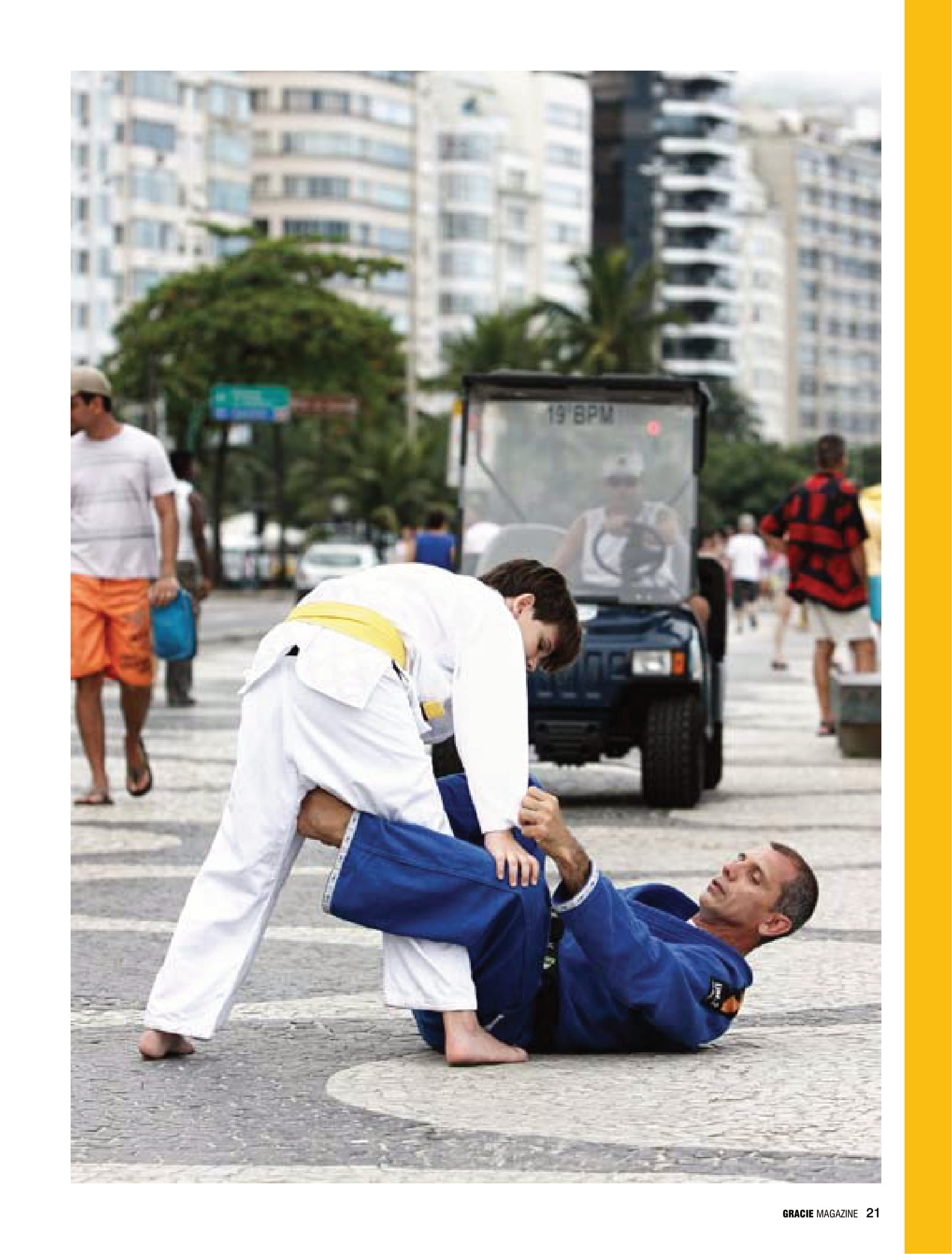

Yes, you don’t remember it, but you were born playing guard. If you stopped practicing it for awhile that’s your doing. After all, the position,

Jiu-Jitsu fighters’ eternal savior in the ring, has been

around for ages. Years. Centuries. Anyone to peer at

the oil-painting masterpiece “Fight at the Cock Inn,” by

Francisco Goya, can observe the following scene: a bar

fight, Spaniards beating each other with clubs all over the

place. At center canvas, a guy seems to have a superior

position… passing the guard! Well, you may need a little

imagination to see that.

But creativity has always

been linked to the guard. In

an obscure book, found on the

shelves of scholarly Gracie Barra

professor Márcio Feitosa, one

can read a theory according

to which African pigmies, in

hand-to-hand combat, valued a

technique of maintaining their

legs between their ferocious

aggressors and their noses. Flailing legs, therefore, have always

been one’s salvation.

It was Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu,

though, that further explored

and valued the guard, as an art of

defense on the ground and one

to even out the weight difference

between the aggressor and the

aggressed upon. More than judo,

sambo or any other art.

But, what about the Japanese? Weren’t they the ones to

create the technique? Aren’t

there schools that prioritize

grappling in judo, the thing they

call newaza? Yes, it’s true. So

then, we’ll ask a specialist like

Carioca Flávio Canto, owner of

the most attacking ground game

in world judo, his view on the

question.

“I think Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

is exceptional. Its great contribution to world newaza, and to the

guard game, was to align a great

number of practitioners with

Brazilian creativity. From there

the whole array of positions and

unprecedented situations, today

a mainstay, came to be,” says the

Athens-2004 Olympic medalist.

“The spider-guard, for example,

I’d never seen before anywhere,

it’s a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu thing.

Another positive aspect of the

art is to land playing guard and

always facing your adversary,

after all no one has eyes in the

back of their head. That’s the

reflex missing for a lot of judokas

and wrestlers.”

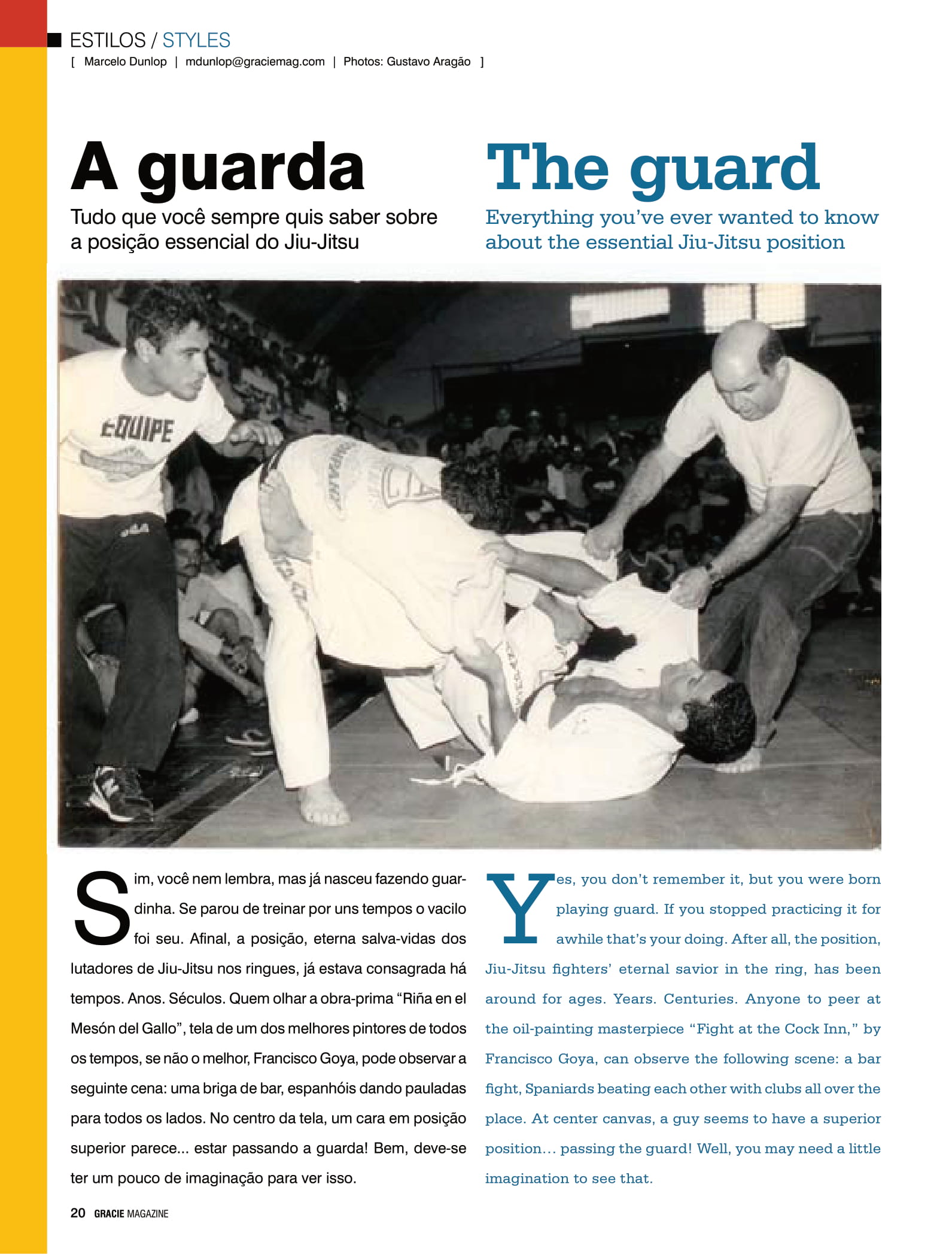

Stone by stone, the

ramparts

When he entered port

in Brazil in the 20th century,

Japanese master Count Koma

didn’t just bring with him an

effective leg game, steadfastly

learned by Carlos Gracie. He

also taught oriental lessons of

discipline, health and honor

that abide in the family’s history forever. Seeking to spread

the art he benefited so greatly

from, Carlos began to make history – and to himself scribe the

history of the guard. “He was

the first westerner to overcome

an eastern champion, in 1924, at

a time when Japanese thought

westerners to be a bunch of

degenerates,” recalls son Rilion

Gracie, considered to have the

best guard in the family (see

interview). It was against Geo

Omori, when the grandmaster

pulled guard and applied a

tomoe-nage, the ever-popular

“circle sweep,” and landed

in the mount. So the Gracie

popped the arm of the valiant

Japanese, who ordered the fight

to continue with the ligaments

of his arm in shreds.

Later on, in 1951, when

brother Helio Gracie closed his

guard and, with his wrists (powerful to this day), put extraordinary judoka Jukio Kato to sleep,

with a collar choke, the art of the

guard came to eminence. And

ready for further development,

thanks to the ingenuity and

sweat of other Gracies, Barretos,

Hemetérios, Machados, Vígios,

Gomes, Behrings, Alves’, Virgílios, Duartes, Penhas, Jucás,

Castello Brancos, Góes’, Vieras,

Santos’ and Silvas. And even a

Stambowsky. Every new faithful

adept at the guard went adding

their contributions, depositing

a stone here, spreading cement

there, and helping to build the

guard’s reputation as being the

essence of Jiu-Jitsu.

The metaphor of building,

in fact, is no gratuity. To Carlos

Gracie Jr., the guard position

is like a fortress providing the

fighter security. You don’t necessarily lose a war just for not

having solid ramparts, but it certainly helps. Including for, from

atop them, posting your arsenal

of attacks: “The guard is the

Jiu-Jitsu fighter’s fortress. You

choose whether to fight with it

open or closed,” he teaches. “In

a war, what’s the most intelligent thing you can do? Start

the war with your gates closed.

In the closed guard, you are

waging war with your enemy

from within your walls. If the

guy opens your closed guard, he

knocks down your drawbridge.

It’s a threshold position, which

obviously demands a new strategy. If he invades, or in other

words, passes your guard and

makes it to your side, the battle

starts to unfold within your

domain, with you much more

exposed. It becomes complicated, you’ll need to use thrice

the strength to defend yourself,

but that doesn’t mean there’s

no way out.”

The shield turns into a

weapon

In Rio during the 1950’s,

Jiu-Jitsu was already famous

for giving any old little guy the

chance to be his own fortress.

Thus, it was Carlson Gracie’s

time to add his contribution

to the guard – first during his

days as a fighter, then with his

students. Competitive to the

extreme, Carlson would have

his students specialize, to win

championships. Those were

the days when he would bellow:

“You’re either a guard player,

or a passer.” Should a reader

inquire as to who were some of

his best pupils, four good guard

players surely make the list: Cássio Cardoso, Ricardo de la Riva,

Sergio “Bolão” Souza and Murilo

Bustamante.

“There’s a myth Carlson

only trained guard passers. But

besides De la Riva, he had another student, Marcelo Duque

Estrada, the Octopus-Man, now

a judge, who had an incredibly

elastic guard,” comments red

and black belt Master Redley Vigio. “Cássio Cardoso, for example, was good all around. But his

guard really left an impression:

all Jiu-Jitsu students should

watch his one-hour fight with

Marcelo Behring, from 1988.

Marcelo too had a phenomenal

guard, and the end is sensational; it’s all on Youtube.”

Both big for those days,

at around 76kg, Cássio had in

the Rickson Gracie student

his greatest rival, and the one-

hour battle between the two

was their decisive bout, held in

Lagoa, Rio de Janeiro. “Carlson

told me to pull guard and tire

him out. I even used a sweep I

learned from Marcio Macarrão,

but at the time it didn’t count on

the score. In the end, I passed

his guard three times and he

passed mine once, 6 to 2 on the

scorecards at the time. Today,

it would be more like 21 to 5,”

Cássio, 46, comments.

Up until 1994, it was not

enough for the fighter on the

bottom to reverse the fight and

land on top to earn points from

the sweep – he had to do it using recognized moves, like the

tomoe-nage, or foot-on-crotch,

or the classic scissor. With the

reform of the rules, proposed by

the newly-inaugurated Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Confederation, all

guard players had to do was

pass and go on top to score

points. Now they were given

their due prestige. And were

ready to surprise.

“The guard, which up until

1994 had been a shield, became

a weapon and could decide the

fight. I remember having seen

in the gym, in 1987, Renzo Gracie playing spider-guard for the

first time. As he was a guy with

a lot of resources, he didn’t use

it much in competition. Me, being skinny, I loved the invention

and surprised a lot of people with

it,” recalls Vinicius “Draculino”

Magalhães, 37. The guard player

show was taking off. The same

year, with his confusing outer

hook placed with his broad and

ductile foot, Ricardo de la Riva

managed to stop the impetus

of the practically unbeatable

Royler Gracie, and gained a

guard named after him. Now

Sérgio Bolão, with a peculiar

guard (lying, with a knee drawn

back at the bend in the adversary’s elbow, while the other leg

would remain free to stand up;

the sleeve was held on the bent

knee’s side, and the other grip

was placed at the knee, creating

a pendulum and sweeping to the

side of the knee pulled back), he

made history and, in good cheer,

inspired a generation of sweepers. With a “bunk knee,” as he

remembers it, Roberto “Gordo”

Corrêa was obliged to improvise and also made his mark on

the art. “The half-guard, which

until then could be considered a

position favoring the athlete on

top, almost as good to attack as

having side control, is today the

perfect position for the guy on

bottom to attack from. There’s

no two ways about it, Jiu-Jitsu

carries on in sheer evolution,”

Carlinhos Gracie observes.

Stiff legs? fine, you too

can be a great guard

player

It’s tough talking about

the position’s evolution without

citing two other out-of-the-ordinary fighters. Roberto “Roleta”

Magalhães, the engineer of the

sweeps, influenced a generation

with new moves, unlikely traps

that would lay waste to, in World

Championships, aces of several

generations – from Wallid Ismail (1996) to Zé Mario Sperry

(1998), to Amaury Bitetti (1999)

to Fernando Margarida (2000).

Not without cause, the three

owners of the most admired

guards in present day – Rubens

Cobrinha, Bráulio Estima and

Roger Gracie – consider him,

Roleta, the best they’ve ever

watched fight. Another extraordinary guard player, with surreal

finishes, was Antonio “Nino”

Schembri, who also breathed a

new rhythm into attacking JiuJitsu – in this case, his idol Elvis

Presley’s rock-and-roll.

Malleable, with strong and

flexible legs, the duo from Gracie

Barra helped solidify the myth

that an effective guard is elastic,

almost magical. Not necessarily

so. The referee in the battle between Roleta and Wallid, at the

1996 Worlds, policeman Sergio

Ignácio was fed up training with

the best guards at Gracie Barra.

A passer of the best kind, strong,

adept at the squashing game,

he ran into a dilemma at brown

belt: “I either learned to play

guard, or Carlinhos wouldn’t

promote me to black belt. That’s

when I revealed my problem to

Renzo, and he provided me the

way off the plateau that dispelled my fear of playing guard:

good guard replacement doesn’t

demand elasticity, flexibility in

spreading the legs – all you need

is to not let the guy past the line

of your knee. This lesson makes

it a lot easier to replace.”

Starting there, your guard

will begin to gain wings. As

revealed by Bráulio “Carcará”

Estima: “When I attack, I do it

from back to front. First I block

my adversary’s defenses for my

attack, and only then do I go for

the fatal assault. They’re tiny

adjustments. The first thing is to

break your opponent’s posture.

Then I work on him and try to

annul his defense, before actually attacking. Thus, if I attack

with a triangle but the guy defends, an arm ends up hanging

out. These days, a good guard

player is not one who defends

his adversary’s best pass, but

one who doesn’t even let his adversary begin to go for his best

pass. You can’t let him develop

his best game. That’s being one

step ahead.”

For you to arrive at an

advanced stage, though, never

forget to build a solid foundation, for your ramparts not to

crumble: “Anyone wishing to

have a good guard should learn

and practice all phases of the

guard,” says Fabio Gurgel, leader of Alliance. “First closed, with

the adversary on his knees, then

with him standing; after that the

classic foot-on-crotch guard and

its variations. Insist on the basics, as later your body type and

style of game will surely define

what’s ideal for you.” There you

have it, now you are ready to

flail your legs, this time doing it

with class.

===

Sergio Ignácio didn’t just

learn to play on bottom, but

earned his black. The sensibility

Renzo demonstrated, though,

is an attribute one can develop

as a guard player, in figuring

out what works for his or her

self. What most unleashes this

sensibility, of course, is flight

time in the gym. But there are

shortcuts. “Jiu-Jitsu is body

and mind,” Redley Vigio conveys. “When training, you use

mostly your body. That’s why

it’s fundamental that one converse after training, and take

notes – even if just mental ones.

It’s when you ask your training

partners: ‘At that moment were

you trying this, when I blocked

you? Or was that what you were

trying for?’ It’s when you go

over the positions in your head

and draw on your instinct and

sensibility.”

===

In the States, Jeff Glover is guard

number 1

Jeff Glover, an American

from Santa Barbara, California, owns the most respected

guard in the USA. Perhaps for

the fact the Ricardo “Franjinha” Miller student trains with

the feared Bill Cooper every

day, at Paragon JJ. Two other

champions that leapt to mind

are Rafael Lovato Jr and Mike

Fowler. A teacher in California

for around 15 years, Cláudio

França named a certain world

champion: “Let’s not forget

BJ Penn, the Hawaiian who is

still defending Jiu-Jitsu’s flag

in MMA.”

===

Lethal Guard

Can the guard itself be

a finishing move? Yes. At

the end of the 1990’s, there

was Renato “Charuto” Veríssimo’s famous kidney guard,

which for the experience and

strength of defenders has fallen into disuse. “The pressure

of the legs crushing the torso

at the kidneys was like being

in a boa’s coils,” says Carlos

Gracie Jr in praise.

One from the old generation, though, guarantees

that in the 1970’s there already was a lethal guard. “The

guillotine guard existed. It

was created by Marcio “Macarrão” Stambowsky: if you fell

into it you were dead,” jokes

friend Alvinho Romano.

Truth is, the elongated

Macarrão was a master in replacement, triangles and arm

attacks. And, especially, never-before-seen sweeps that

landed him in the mount.

Now living in Connecticut, USA, and living out a

dream, “of making a living

through Jiu-Jitsu,” he teaches

how the secret to being a

good guard player is body and

abdominal control. “I learned

from Rolls that the guard is

more than a defensive position. We called it combative

flexibility.”

===

Rilion professes

Rickson Gracie always said

you have the best guard of

the family. What makes a

guard good?

The guard has always

been a way of evening the playing field in a fight between two

people, bringing the fight to

the ground, where a 60kg guy

balances out the strength difference and even goes on to have

better chances of surprising the

120kg guy.

When I got my black belt,

25 years ago, I weighed 59kgs.

And I always had the winning

spirit, understood my family’s

Jiu-Jitsu to be an art of selfdefense, but one with the objective of submitting the adversary.

The same way these days we

see hundreds of scrawny guys,

with good guards for lack of

other options, the same went for

me. The guard is the salvation

of the weak.

How did you go about developing your game?

Guided by Rolls, Carlinhos,

Rickson, Crolin, professors who

I mirrored, I realized I had to

have a really good guard to face

anyone, but a complete guard – I

wasn’t interested in just holding

out against opponents, defending myself without managing

to do anything in the fight. But

the first idea that clicked for me,

at blue belt, was: if I can’t manage to neutralize the guy with

the guard, with which I have

millions of options of barriers,

my legs and hands and all, if

he passes I’m dead – I have to

exert triple the force, and on top

of that with the guy’s weight on

my chest, squashing my neck

ears. So my first concern is not

to lose.

And what was the second

stage?

At purple belt I was already

real flexible, and with a guard

famed for being unpassable, at

the little championships. But it

happens that I’d win because

the guy on top would wear out,

and ended up leaving openings for the triangle, or I’d end

up on his back and such. So, I

went on to the next stage, developed at brown: to reconcile

defensive with attacking guard,

incorporating a varied game of

submissions from the guard,

sweeps and taking the back.

That’s when my Jiu-Jitsu started

improving on all fronts, because

I started landing on top of my

adversary, and I had to make the

most of the favorable situation.

These days, I think I’m better on

top than on the bottom. I prefer

playing on top – my objective is

to jump the fence and attack my

adversary.

What other tricks do you

have for making adversaries fall into traps in the

guard?

One kind of guard is that

where you grab onto the sleeves,

tie up the guy’s arms, but you

can’t do anything either, and it

becomes an ugly fight. Another

is the guard where you give the

guy a little taste. He sees his

chance to pass, exerts force but

doesn’t pass. I specialized in

that, in leaving openings for the

guy to pass – and there he either

exerts force and tires, or falls into

some trap.

Because I don’t believe

there are humans who don’t

tire. The best prepared guy in

the world, confronted with the

right technique, executed to

perfection, he will be forced to

apply force, and at some point

will wear out. Everyone has

their limit, it’s up to you to find

the method and path to pushing

your adversary to it.

Which is your favorite

guard?

Jiu-Jitsu to me is easy and

effective. It’s that which you can

teach any student who walks

into your gym, otherwise they’ll

pick up their things and never

come back.

I look to play guard right

at the guy, at least in my way

of fighting. I try to keep the guy

worried about getting submitted the whole time, fearing getting tapped out. Even if the guy

knows how to defend, the worry

will fatigue him, exhaust him.

And when he makes a mistake,

he gets caught. The better your

adversary’s technique, the more

you need to worry him.

So, of course I’ll even play

half-guard, sometimes. But, if

the adversary is really good, after I sweep him he will still put

up a fight from the bottom. So

then one gets a sweep here, the

other gets one there, and then it

becomes that fight we’re seeing

in competition these days. Of

course, you need to know your

objective when playing guard. If

it’s to sweep for points, perfect.

But I don’t want my opponent

only to be concerned with not

getting swept. He has to feel

threatened the whole time.

Is there any bad type of

guard?

I respect all positions. If

I teach a technique to ten different people, I know that, as

much as I’d like it to be otherwise, each student will be more

suited to one aspect and not the

other. Jiu-Jitsu is an infinite art;

a shorty won’t have the same

game as someone with long legs.

That’s why a master can’t go

blindly labeling one guard bad

and the other good. The secret

is to make out the weaknesses

and virtues of the position, never

condemn, arrogantly. Now, the

guy who wants to be a reference

in the guard cannot just know

one guard. He has to know other

paths, for the day he encounters

a rock in his way.

What do you consider to

be your guard’s greatest

achievement, Rilion?

The Jiu-Jitsu rankings

from my day, 20 years ago, were

molded in training, from the

visits we’d pay to each other’s

academy. There were no World

Championships, none of that. If

you look at it in terms of titles,

really, who was Rilion Gracie?

What do I have on my CV? So I

didn’t do anything for Jiu-Jitsu?

Wrong. Yes, I did.

There were times I’d be on

the beach and some tough guy

from another school elsewhere

would show up, I’d speak for us

here, and we’d decide: “Shall

we go grab a gi and train?”

And we’d bust each other up

in the gym, and it wasn’t just

me, ’twas a lot of people in my

day. Just with me it happened

so many times I’ve lost count.

I won’t name names; that’d be

unethical. So my CV’s like this,

brother. From my 20’s till my

40’s, I never tapped to anyone,

in these training sessions, and

I faced all the best guys of my

day. Truth is, I haven’t tapped to

this day, but these days I’m not

in any condition to take on the

top guys, you know? I stay away

from them…

What’s your challenge

these days, when training?

To save more energy than

before. I’m better technically,

more experienced, but I’m not

the Rilion of 15 years ago. I feel

good for my age, of course, and

know a Rilion of 35 would fatally defeat a Rilion of 25. But

nowadays, at 45, I don’t recover

as quickly as I did. Back in the

day I’d push the pace, take

two breaths and be ready to

go again for 20, 30 rolls. I know

physically I’m in the process of

decay. At the same time, the

more flight time, the more microscopic subtleties you have.

For example, you start developing a sensibility where you can

guess your adversary’s thoughts.

A second before the guy makes

a move your hook is in there

blocking him. That’s what JiuJitsu’s about. Without sensibility, without a certain spiritual

connection to the art, you win

on conditioning, durability, and

you’ll always be coarse, someone

with ugly style.

Was Rolls Gracie the link

between the guard of

the past and the modern

guard, the same way he

was the bridge between

traditional and modern

Jiu-Jitsu?

Without a doubt. When

Jiu-Jitsu fell into Rolls’s hands, it

evolved 50 years in ten. He took

a Beetle and made it into a Ferrari, and dropped it in our hands.

Of course, the wheel, headlights

already existed. But it was with

Rolls that the guard went from

being defensive, waiting for the

opponent, to a position with an

arsenal of attacks.

He had a really open and

dynamic mind, always paid attention to the student, and liked

listening to them, to see new

positions. Now you take a guy

in the spotlight and it seems

you have to plead for the love

of God for him to teach you a

position. So it was Rolls who

created what was, to me, the

golden generation of Jiu-Jitsu:

Carlinhos, Crolin, Rickson and

so many of Rolls’s students from

outside the family.

I learned a lot about the

guard watching one of them

train, a guy called Talarico, who

even had short legs.