[First published in 2016.]

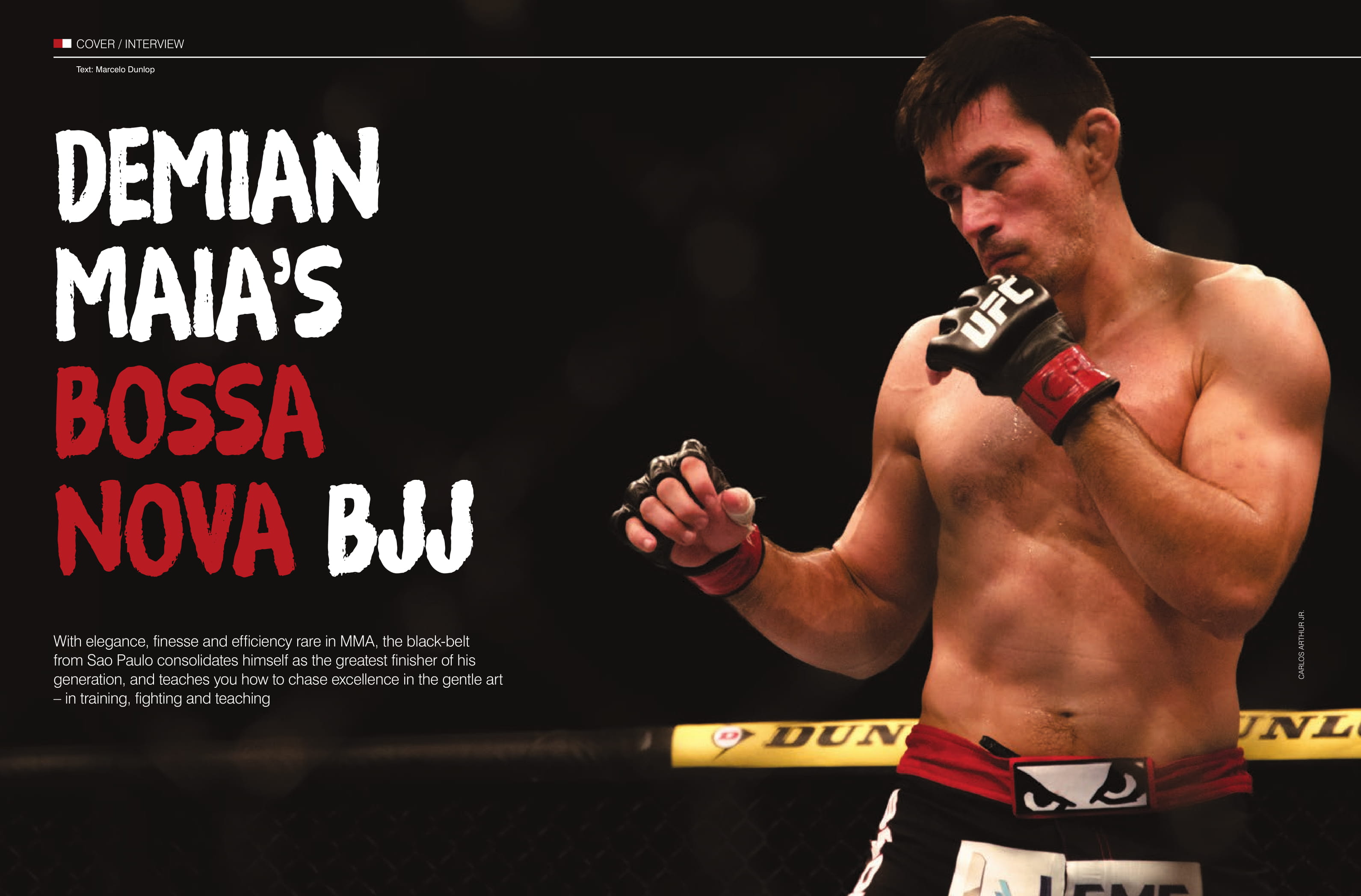

With elegance, finesse and efficiency rare in MMA, the black-belt from Sao Paulo consolidates himself as the greatest finisher of his generation, and teaches you how to chase excellence in the gentle art – in training, fighting and teaching

Thirty-eight-year-old Demian Maia often connects BJJ to popular Brazilian music, in accordance to a clever comparison he once heard when fighting abroad. “I’m Brazilian, but when I fight I feel like a representative of the jiu-jitsu nation. Even when I fight abroad, I feel the support of the people who train BJJ – not just from Brazilians, or from Americans or Europeans. It’s a sport that generates a lot of passion. Once I heard a guy say that, after bossa nova, jiu-jitsu was one of our biggest cultural exports – one of the most important ones, with the biggest repercussion abroad,” says the UFC welterweight, who currently has 30 fights (24 wins – 12 submissions – with six losses).

Like in music, each artist has their style. Rodolfo Vieira and Marcus Buchecha, idols of modern BJJ, could be tuba players, smothering people with lots of weight and pressure. The light Miyao brothers would be untamable flautists, always ready to enter the song when least expected. UFC braggadocio Conor McGregor would be a pianist who plays standing, stepping on the keys and mooning the audience. But not Demian: he is a sober, smooth violin player – melodious like few others, with a style able to enthrall the crowd and tame the brutes.

During a tour of Europe, the black-belt talked to Graciemag and gave us the following interview.

GRACIEMAG: You are one of the MMA fighters who best follow the Gracie philosophy, not just because you submit opponents on the ground, but because you manage to be an athlete and teacher at the same time, helping spread the seeds of the gentle art like the family have been doing since Carlos, Helio and Carlson. Besides, your fights are true lessons on fundamentals. What is the secret to balancing the double life of teacher and athlete?

DEMIAN MAIA: In BJJ, usually the fighter is an athlete and teacher. In other fighting sports – like judo or boxing, for example – the professional athlete almost never teaches; they just train and compete. I have been teaching since I was a blue-belt. When I got into the UFC, I still directed training daily at my gym. After my second fight, I left my students teaching the team, and I practically stopped teaching. For a few years, I only did seminars and some rare classes. I always heard that the big problem for BJJ athletes was that they could not be just athletes – that they had to teach class to survive, and that that was bad for their career… For a while I believed that, because I looked at all my UFC colleagues and saw that very few were teachers. So I tried to be like everybody – I taught almost no classes. However, in 2014 we opened Vila da Luta – a partnership of mine with entrepreneurs Marcelo Zanin (also a black-belt) and Patricio Santelices, besides my head coach and manager, Eduardo Alonso. It was a big investment by us all – financial, of time, emotional. I felt the responsibility to get involved again with the teaching side of BJJ. It wasn’t just a will to be involved in more training, but also to shape teachers, trying to have a closer relationship with the students, trying to offer the best possible service.

Who taught you how to teach?

I learned how to be a teacher from the best, like Fabio Gurgel, Leonardo Vieira and Fernando Tererê. I had access to the best techniques and exceptional didactics. I think it is my obligation to teach. Besides, every time I teach, I understand the techniques better and learn something new. I evolve faster than by just training. Besides, seeing people signing up for the gym and benefiting from what our martial art offers is priceless. Today I feel that my mission is to divulge BJJ, as both a fighter and a teacher.

Between 2012 and 2015, in spite of dominating on the ground at the UFC, you weren’t reaching the submission. You went as far as to state that you were going to focus more on the mount and try to use more elbows and fists to force your opponents to turn their back. Aside from that, have you honed some other aspect of your BJJ?

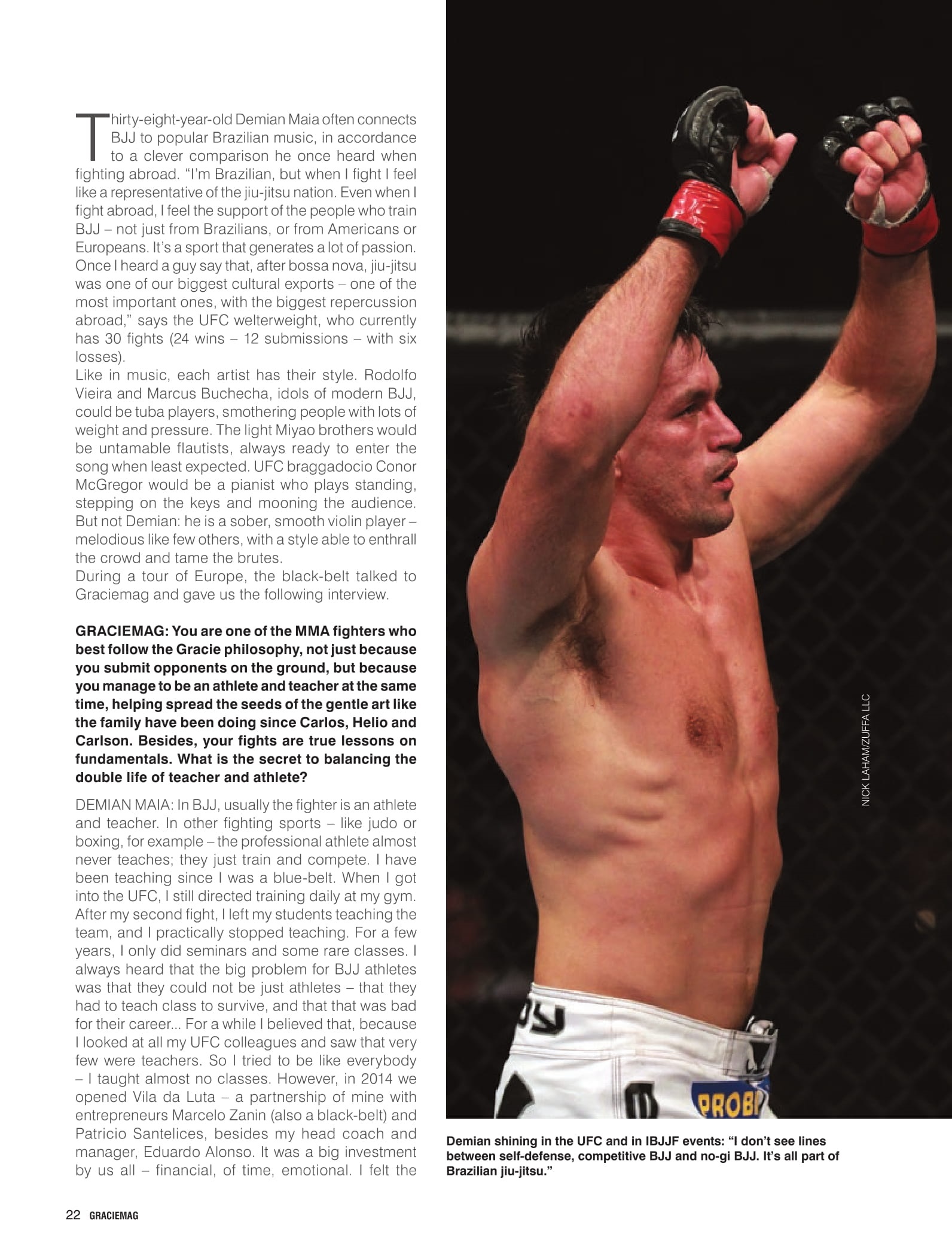

That which you mentioned was one of the things I honed. I don’t see lines between self-defense, competitive BJJ and no-gi BJJ. It’s all part of Brazilian jiu-jitsu. When I’m developing punches and elbows from the mount, I’m improving my BJJ. I have also been very focused lately on improving the finishes from the back. I was getting there and controlling the position well, but was having a hard time finishing. Many don’t notice, but the glove is a major hindrance. Besides, I always strive to practice the takedowns, controls, submissions from the mount a lot.

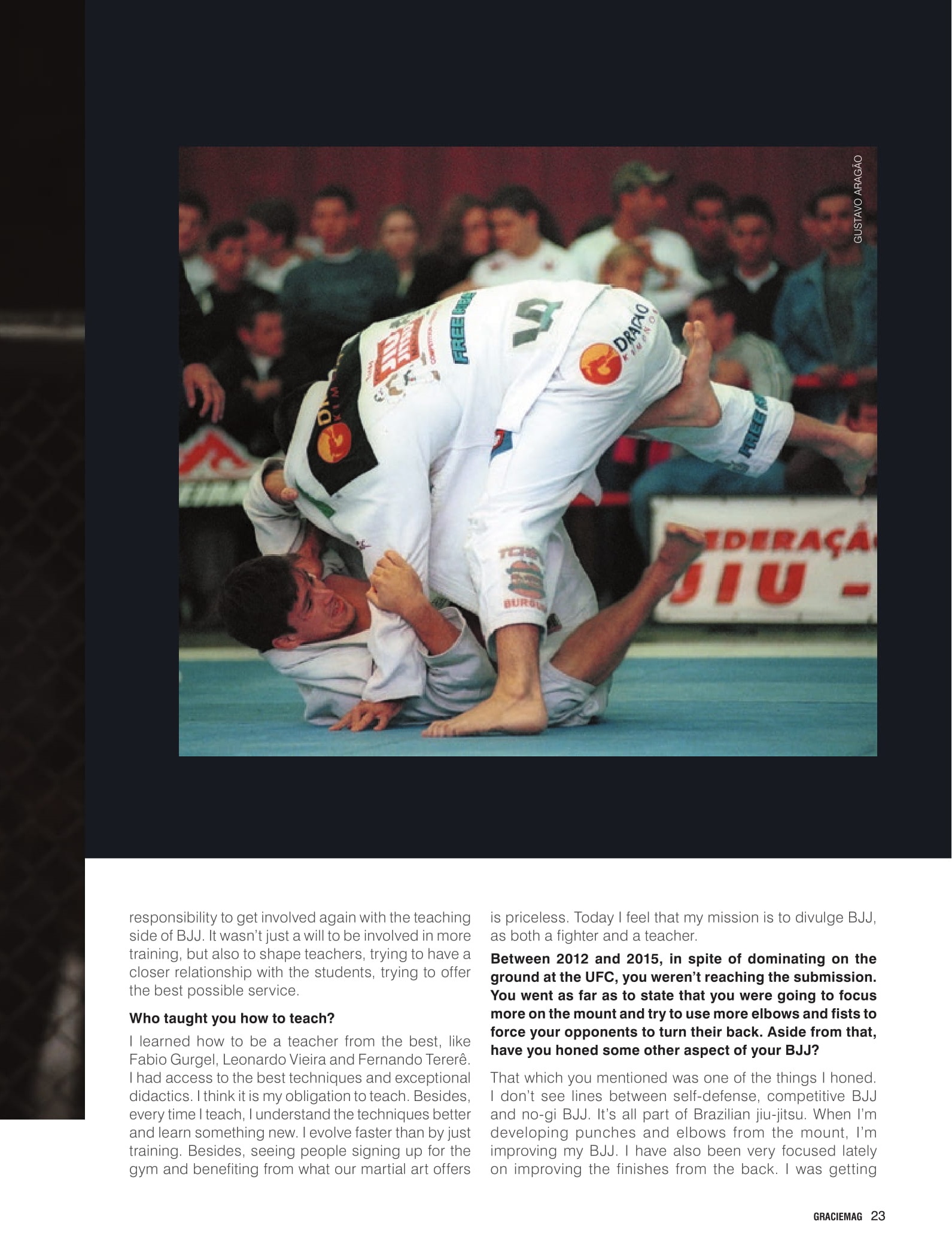

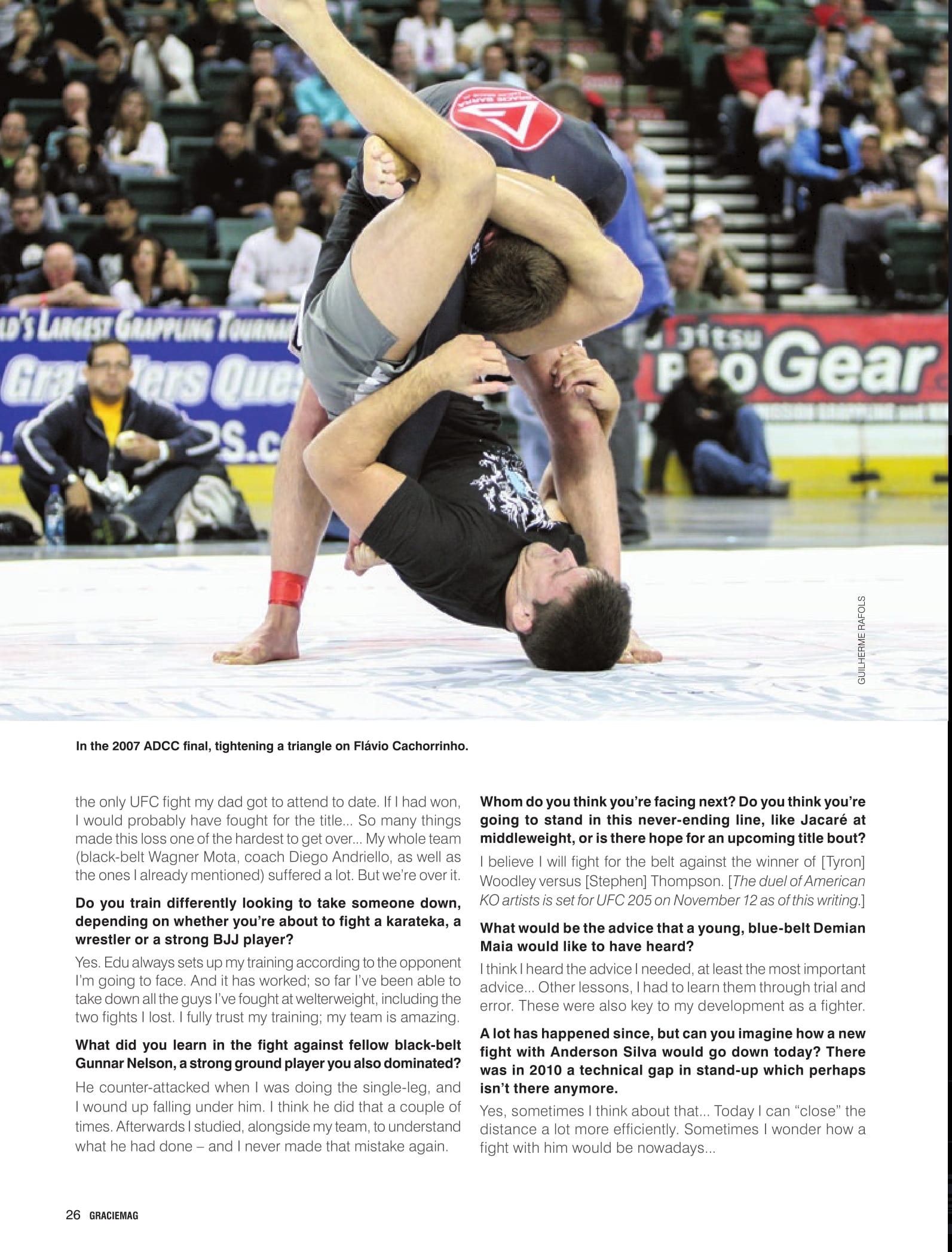

At ADCC 2007, the traditional no-gi event, you won the 87kg division in fulminant fashion. In the 2005 edition, you were only stopped by Ronaldo Jacaré in a very close fight. What did you learn from that experience?

The experience the ADCC gave me was incredible, just like the World Championships, World Cups, Brazilian Nationals… Competition experience counts a great deal when you get in the UFC. When I got in the UFC, I had only six MMA bouts and managed to beat guys who had many more than I did. I credit that to my experience in competitive BJJ, in and out of the gi.

Today you are part of a lineage of respected Brazilian submission experts in the UFC such as Royce, Minotauro, Jacaré and Werdum. How do you view your game in relation to those four?

I believe my game is closer to Royce’s, though a little more developed standing. I have trained and still train a lot takedowns, boxing and Muay Thai. And, when I say boxing, I don’t mean just trading punches; I’m talking about moving, walking. Many people think that training stand-up is all trading punches and kicks. Knowing how to be at the right distance to trade strikes or clinch is more important. I owe a lot of that to Edu Alonso, who made me understand that fighting on the feet is not just brawling; it’s a lot more than that. And also to my stand-up coaches: Ivan de Oliveira (boxing), Dave Esposito and Kody Hamrah (wrestling), and Anderson Coelho (Muay Thai).

Once, fighter Herbert Burns said you seem to fight in a tuxedo, given your tremendous class when performing in the UFC. How do you view this clash between class and education on one side, and taunting and disrespect by guys like Conor McGregor, who sell lots of pay-per-view? How to go on being a martial artist and conquer public opinion and also the public’s attention?

I think everyone has their own personality. At the end of the day, we’re talking about a sport; what matters is winning. Conor may have that way of his, but he gets in there and wins. If he talked a bunch of rubbish and didn’t win, nobody would want to see him in action. I find him good for the sport; he attracts that public that enjoys conflict. But there’s an audience for everything. There’s an audience for the trash talker, the funny guy, the martial artist, the shy athlete… No doubt the trash talker sells, but he also sells because there was a lot of marketing by the UFC. Other types of personality can sell as much as Conor, especially with the marketing push he had. After all, human beings are not made up of just one type of person. One audience identifies with Conor and will pay to see him. Others won’t, because they’re not impressed. I believe, thinking long-term, if the UFC wants to reach all types of audiences, it will have to invest in marketing all types of fighters, all types of personalities. The public buys into a spectacle. Have you seen a spectacle with only villains?

Perfect. And do you think that Conor brought in fact something new, technically, to MMA?

I consider McGregor very good technically. The stand-up moving, distance control, variations in punches and kicks. But, as to technical novelty, I can’t say.

What was your most painful, most instructive loss to date?

I think the one to Jake Shields, in 2013, was the hardest one to digest. Many factors made that loss very painful. I think I won, but the judges ended up giving him a split win. Besides, it was my first UFC in Sao Paulo, my home. I was the main event and I don’t think I fought my best. I made many mistakes. Many people present were my friends, and it was

the only UFC fight my dad got to attend to date. If I had won, I would probably have fought for the title… So many things made this loss one of the hardest to get over… My whole team (black-belt Wagner Mota, coach Diego Andriello, as well as the ones I already mentioned) suffered a lot. But we’re over it.

Do you train differently looking to take someone down, depending on whether you’re about to fight a karateka, a wrestler or a strong BJJ player?

Yes. Edu always sets up my training according to the opponent I’m going to face. And it has worked; so far I’ve been able to take down all the guys I’ve fought at welterweight, including the two fights I lost. I fully trust my training; my team is amazing.

What did you learn in the fight against fellow black-belt Gunnar Nelson, a strong ground player you also dominated?

He counter-attacked when I was doing the single-leg, and I wound up falling under him. I think he did that a couple of times. Afterwards I studied, alongside my team, to understand what he had done – and I never made that mistake again.

Whom do you think you’re facing next? Do you think you’re going to stand in this never-ending line, like Jacaré at middleweight, or is there hope for an upcoming title bout?

I believe I will fight for the belt against the winner of [Tyron] Woodley versus [Stephen] Thompson. [The duel of American KO artists is set for UFC 205 on November 12 as of this writing.]

What would be the advice that a young, blue-belt Demian Maia would like to have heard?

I think I heard the advice I needed, at least the most important advice… Other lessons, I had to learn them through trial and error. These were also key to my development as a fighter.

A lot has happened since, but can you imagine how a new fight with Anderson Silva would go down today? There was in 2010 a technical gap in stand-up which perhaps isn’t there anymore.

Yes, sometimes I think about that… Today I can “close” the distance a lot more efficiently. Sometimes I wonder how a fight with him would be nowadays…

5 LESSONS LEARNED BY DEMIAN THROUGHOUT HIS CAREER

• An open mind is essential

“No BJJ position can be called inefficient in MMA. I remember very well that in the late 90s people used to say that the omoplata didn’t work in a real fight situation, until Rodrigo Minotauro came along using the omoplata with efficacy. I believe everything works – with the exception, of course, of positions where the fighters grab the cloth. It’s just a matter of adaptation. Of course there are easier and harder positions; the key is the open mind to try it.”

• Never lose the habit of repeating the basics in training

“I notice that in gyms there are positions and fundamentals that people look at again very seldom. I give basketball as an example. Even in the NBA, at the highest level, every day the players practice the layup, right? In BJJ it has to be like that. I understand it is normal to move on to practicing more often the positions of so-called competitive BJJ, and then the training starts almost always on the ground, or with the two practitioners standing and grabbing each other. But there are crucial stand-up positions in BJJ, because they teach the base, standing posture, details for walking while one tries to parry a punch, correct positions for not losing one’s balance in a fight situation, etc. That is, they are elements of a fight that must be studied too. That’s why in my gym I like starting the session by going over the basics, which includes techniques for defending against aggression. I have implemented a system in my gym where in every class the student repeats basic positions, both standing and on the ground, in order not to be caught unprepared on the streets, and what’s great is that they learn and warm up their muscles at the same time. Repeating the fundamentals is important because, in time, the fighter specializes in one type of game and ends up never repeating that basic technique which is often paramount and may save them.”

• Trust BJJ, and it will save you

“At the start of my career, when I wasn’t even 20 years old, I went to fight in Venezuela. I remember my first opponent had disappeared, said he wasn’t going to fight, and then that huge guy showed up, Raúl Sosa. That is, I was expecting a 90kg opponent, and a 120kg one showed up. I was concerned, but it all worked out, and I managed to take him down and reach the back, I placed the hooks and punched. Then the ref stopped it – technical knockout.”

• Cherish the friendships made along your journey

“At the beginning of my career, still as a BJJ competitor, money was a big problem for me. The toughest parts were the costs of traveling to compete. The good championships were in Rio, and the money for the bus and food were barely there; I couldn’t afford a place to stay. I had the good fortune of having a friend from school, Rubens, whose dad lived in Rio, and I would stay at his place. I stayed there tens of times. Even when my friend couldn’t go, I’d call, and his dad always welcomed me. I’m very grateful to them; I don’t know whether I would have gotten where I did without that help. Gratitude and hospitality are certainly parts of the jiu-jitsu culture.”

• You lost? Stop complaining – train more!

“One of the big turning points in my career was the loss to Anderson Silva in 2010. Since I could not put Anderson on the bottom, at the Abu Dhabi UFC, I saw I had to improve my wrestling. I did a six-week camp in Chicago and evolved a bunch. I trained with great guys, like former fighter Sean Bormet. I evolved a lot in trying to overcome the flaws from that 2010 combat.”

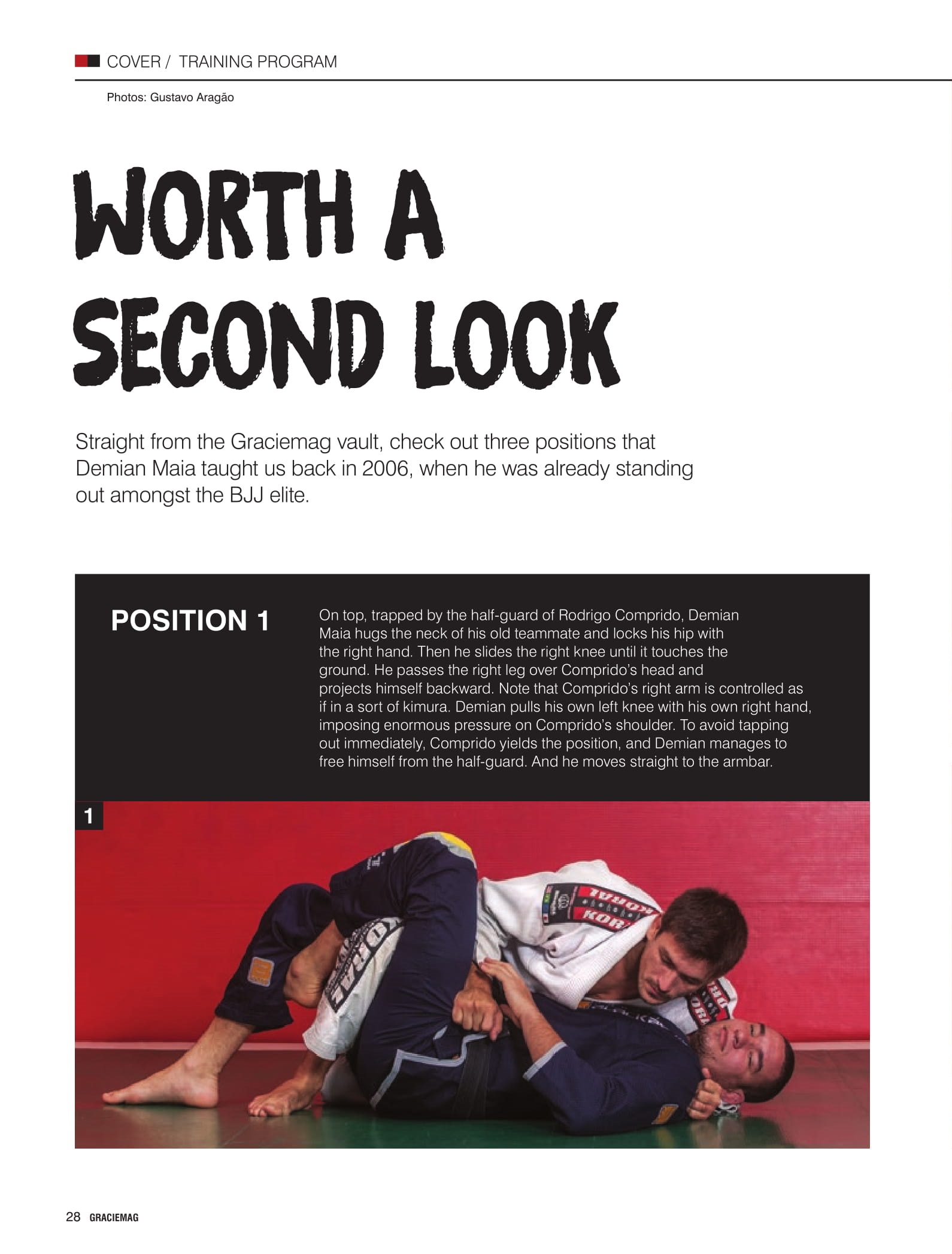

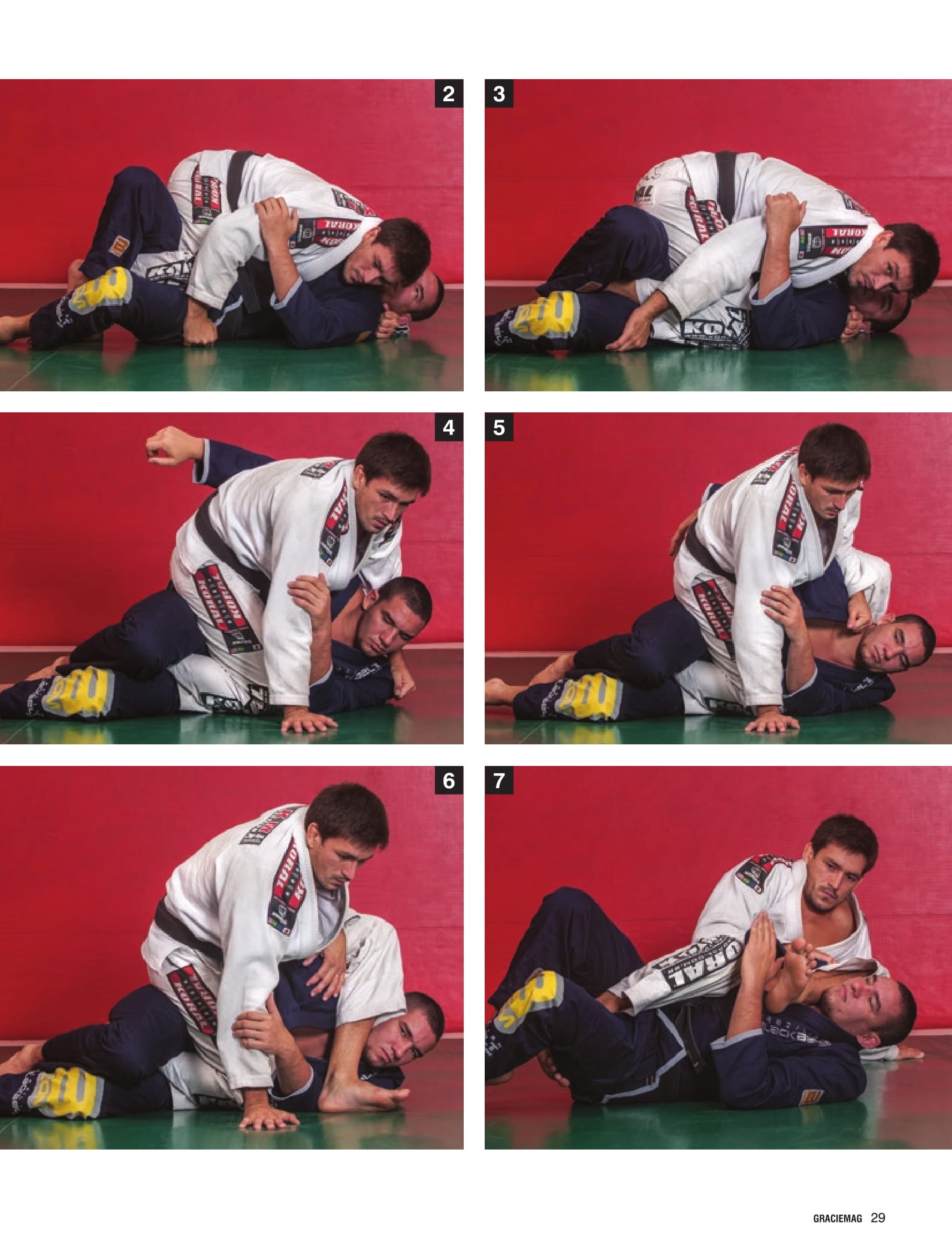

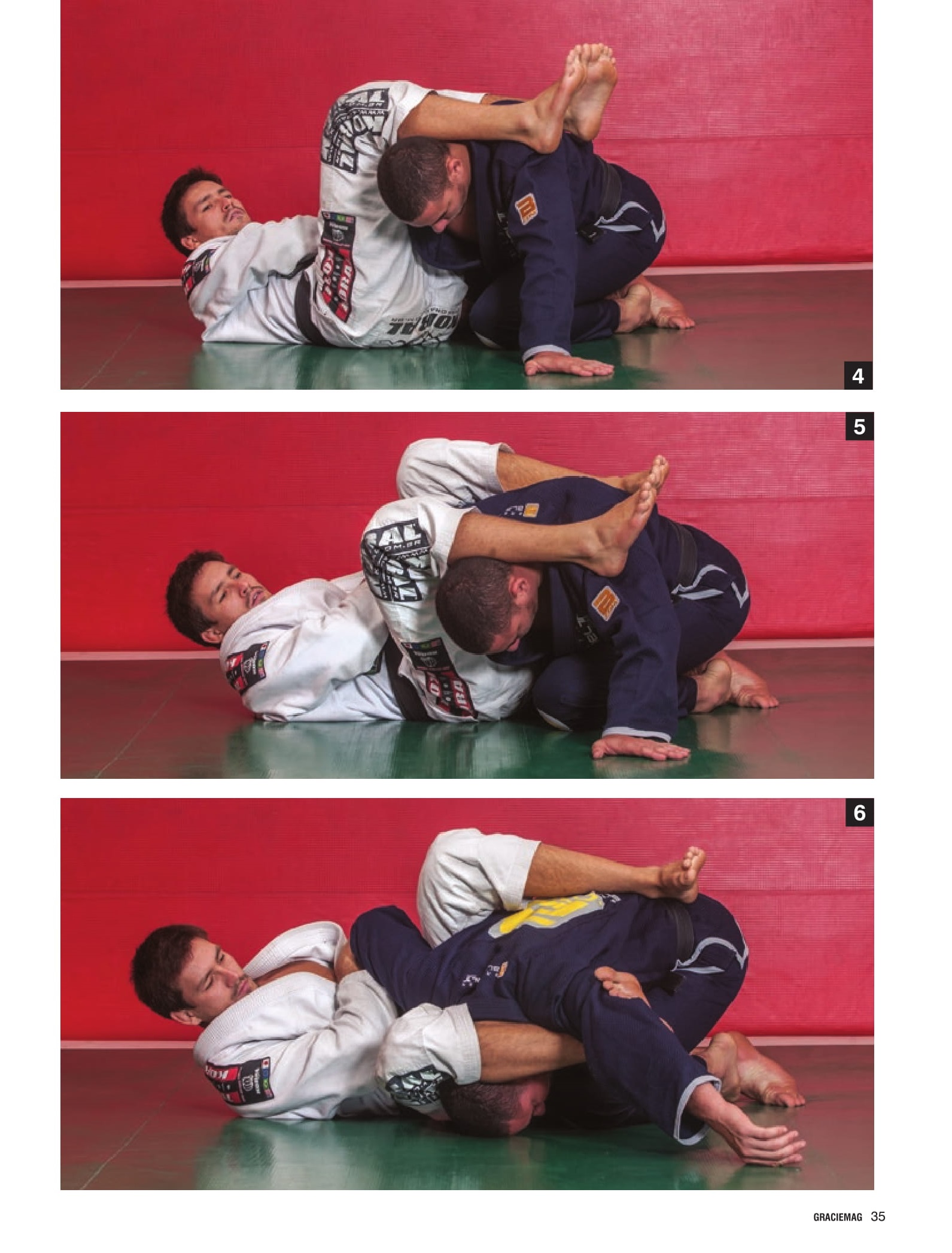

POSITION 1

On top, trapped by the half-guard of Rodrigo Comprido, Demian Maia hugs the neck of his old teammate and locks his hip with the right hand. Then he slides the right knee until it touches the ground. He passes the right leg over Comprido’s head and

projects himself backward. Note that Comprido’s right arm is controlled as if in a sort of kimura. Demian pulls his own left knee with his own right hand, imposing enormous pressure on Comprido’s shoulder. To avoid tapping out immediately, Comprido yields the position, and Demian manages to free himself from the half-guard. And he moves straight to the armbar.

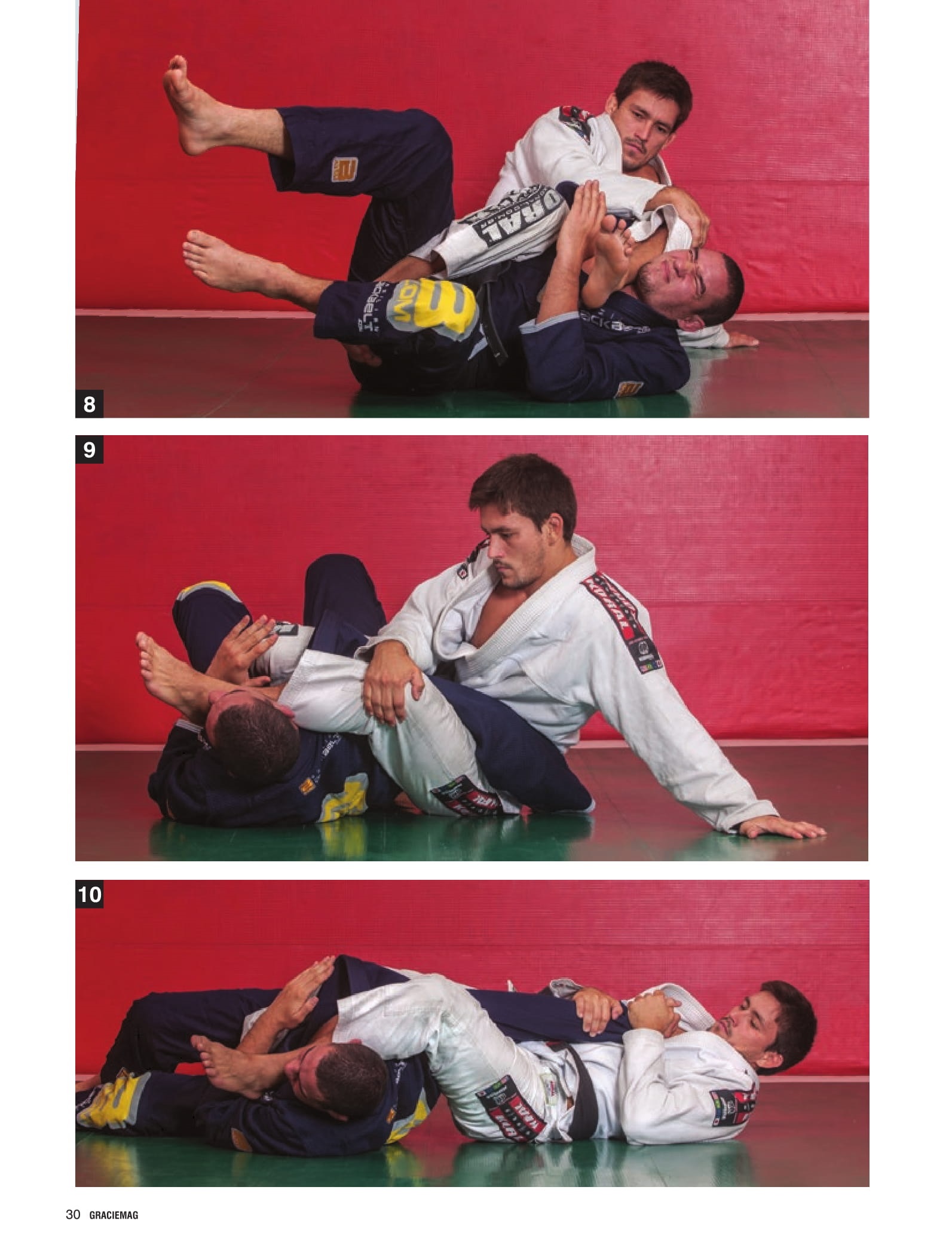

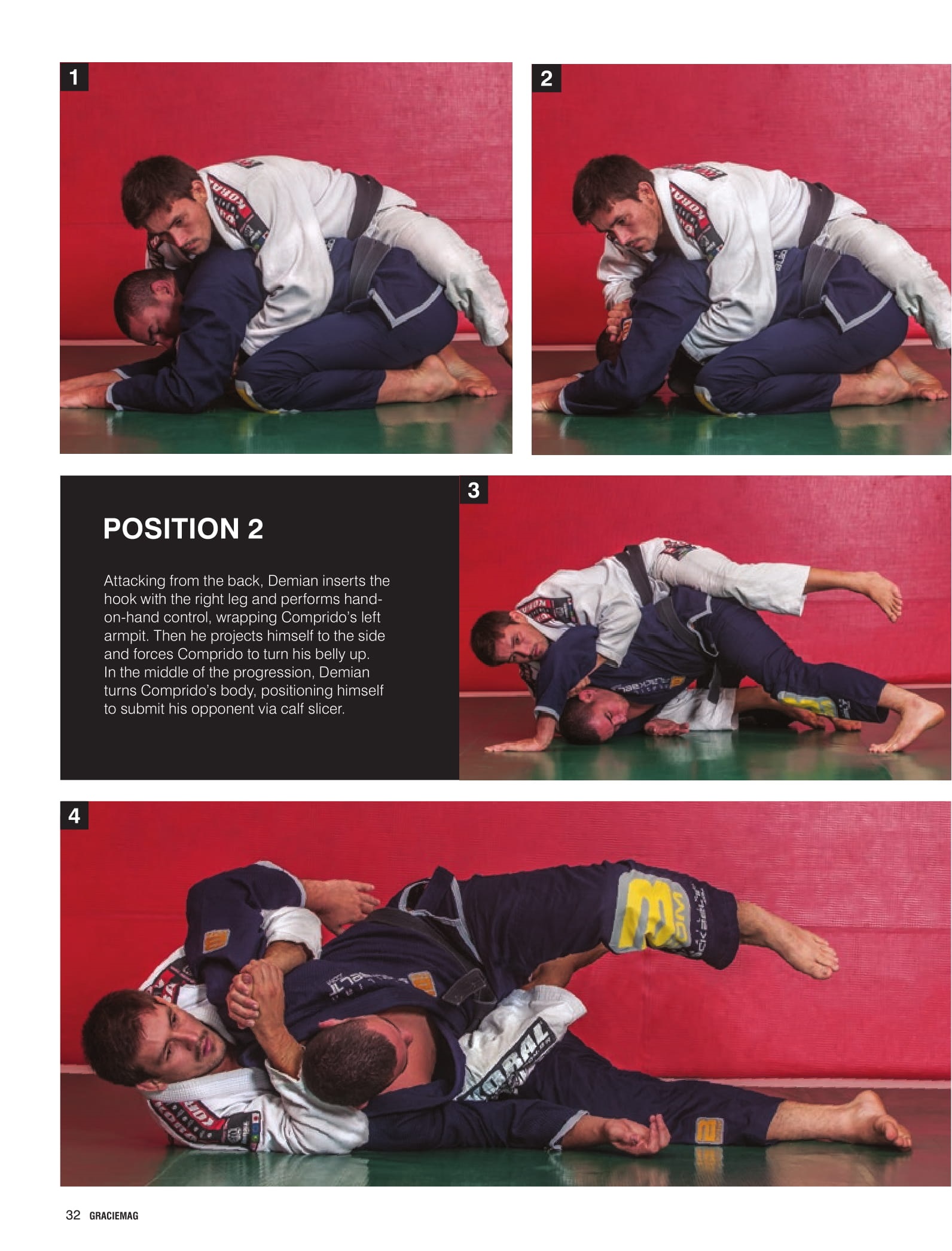

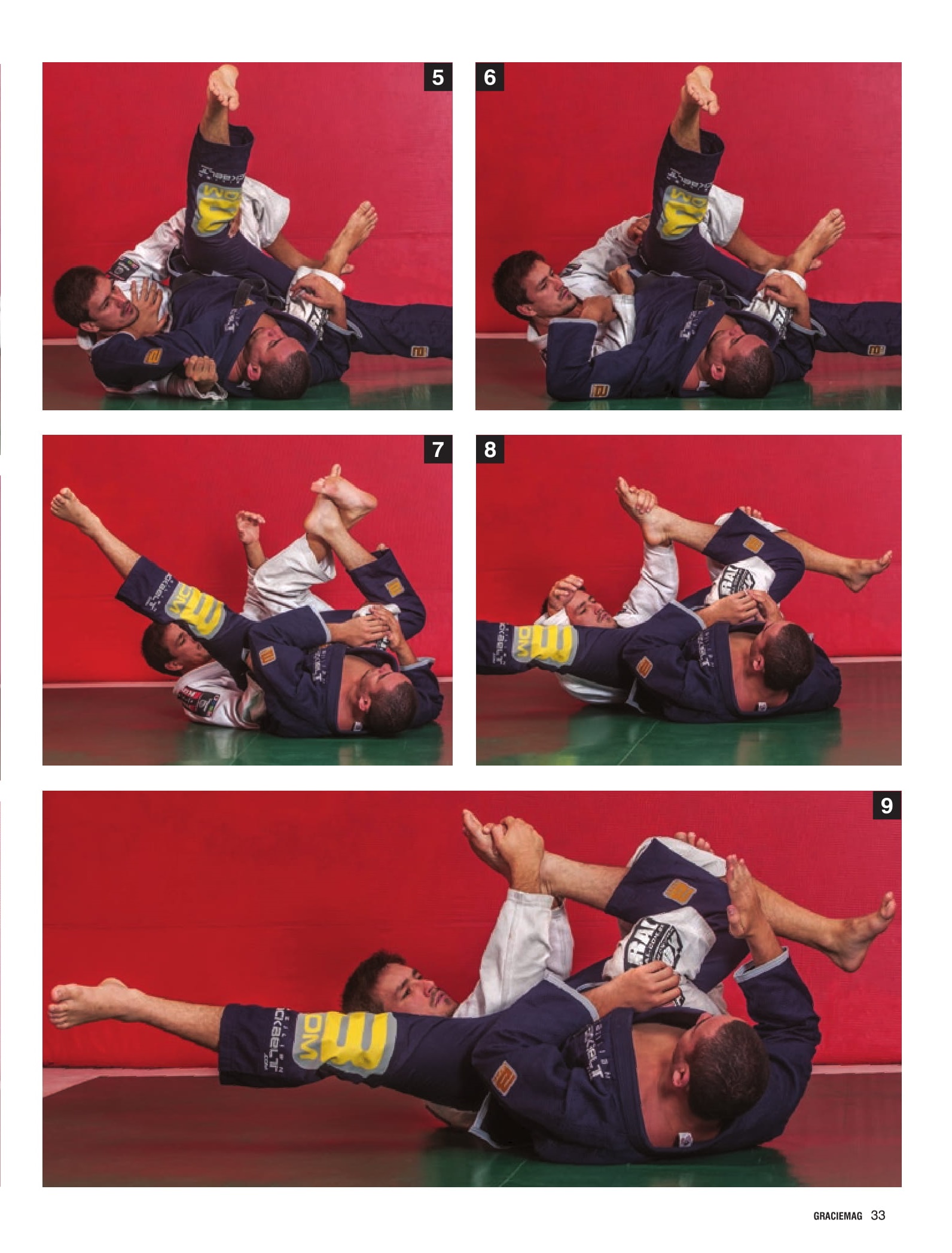

POSITION 2

Attacking from the back, Demian inserts the hook with the right leg and performs hand-on-hand control, wrapping Comprido’s left armpit. Then he projects himself to the side and forces Comprido to turn his belly up. In the middle of the progression, Demian turns Comprido’s body, positioning himself to submit his opponent via calf slicer.

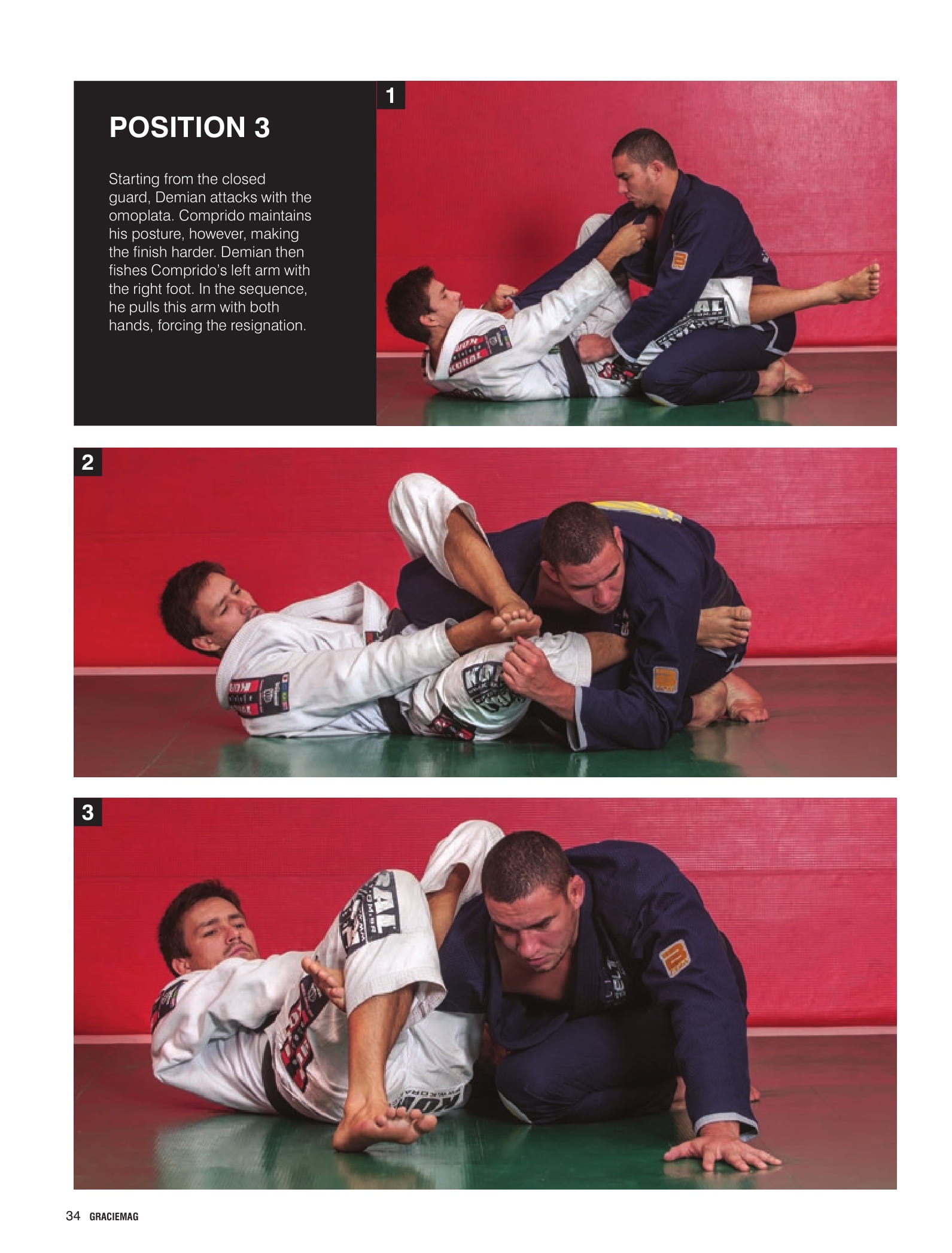

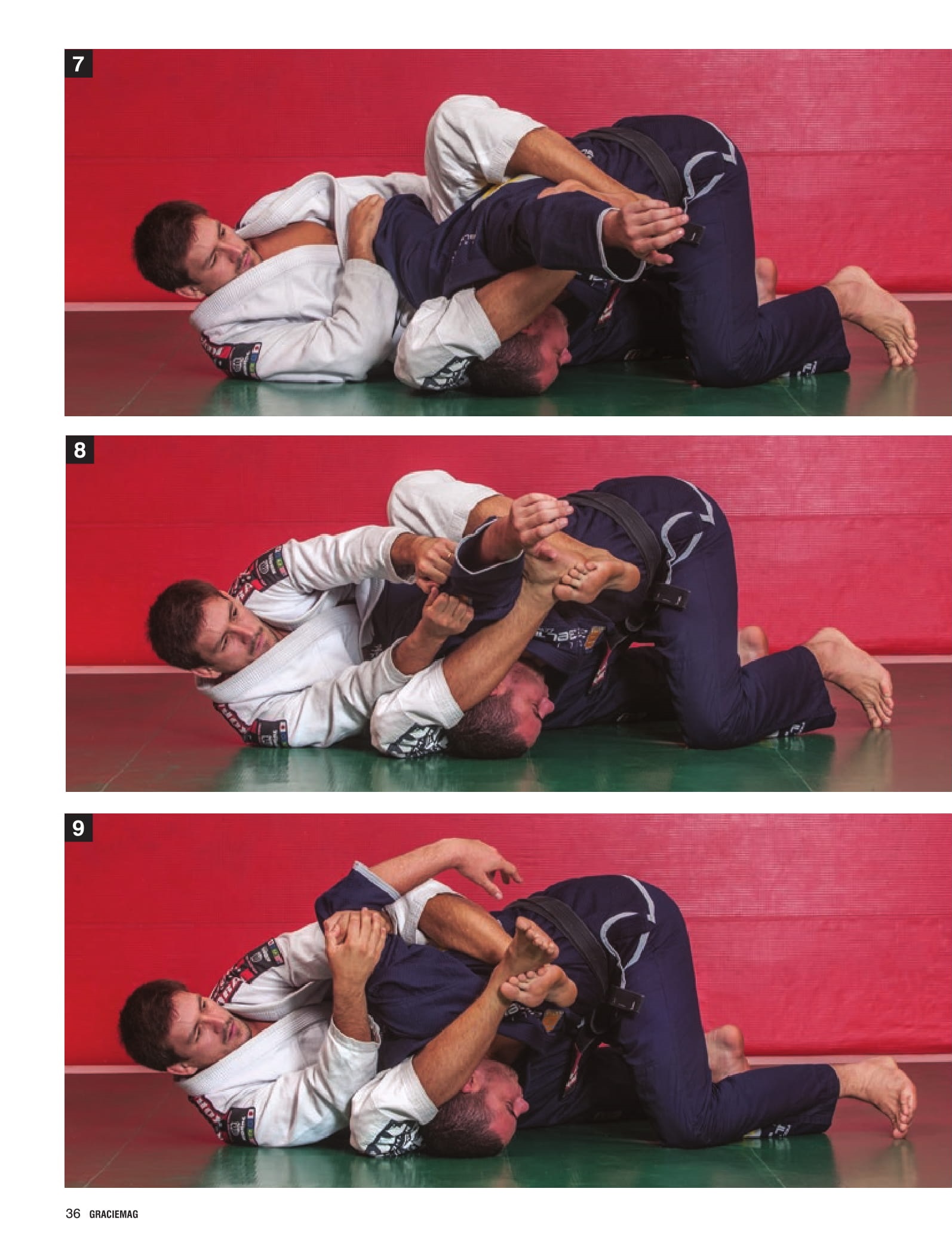

POSITION 3

Starting from the closed guard, Demian attacks with the omoplata. Comprido maintains his posture, however, making the finish harder. Demian then fishes Comprido’s left arm with the right foot. In the sequence, he pulls this arm with both hands, forcing the resignation.

The post Demian Maia’s bossa nova BJJ first appeared on Graciemag.