Leonid Gatovskiy, one of BJJ’s pioneers in Russia, got his black belt from Renzo’s hands.

When black-belt Ali Magomedov pulled guard, swept with help from the lapel and then finished Bruno Frazatto on June 30th in an ACB event in Moscow, many people may have found it weird. “A Russian who knows his levers and wins without a single takedown?” Yup, it’s true: BJJ has been reaping riper and riper fruits in the land of competent judoka Vladimir Putin. But the seeds were planted some time ago.

Indeed, the first time the Graciemag team tried to map BJJ in the host country of the 2018 World Cup, there wasn’t even one black-belt there.

The year was 2011, and our director, Luca Atalla, disembarked at Domodedovo airport to follow a camp organized by Gracie Barra Moscow in the pleasant village of Chelnavka.

Igor Gracie, the teacher recruited for the seminar, soon saw the difference in culture when a very helpful blue-belt asked to roll with him. It was that same Ali Magomedov, at the time a 19-year-old student of engineering hailing from Dagestan, whose environmentalist dad had quite the eventful like. “My father was once attacked by a pack of hyenas in Africa, and had to defend himself with just a torch.”

Brave like his old man, Magomedov would win his black belt one year later, and today he is one of Russia’s biggest names in the gi, alongside Abdurakhman Bilarov, Ayub Magomadov and some other talented competitors.

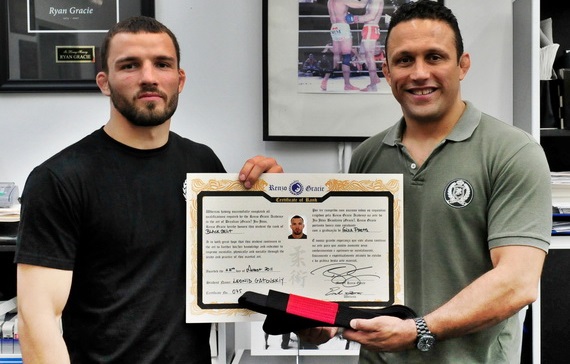

Soon after Graciemag’s journey, Russia would have its first BJJ teacher: Leonid Gatovskiy, who had begun training in Poland and would go on to be made black-belt by Renzo Gracie in New York. The story of the pioneer Leonid illustrates how, little by little, the sport gained traction in the country of Tolstoy.

“I practiced a bunch of martial arts, like traditional European ju-jitsu,” he said. “One day, in 2002, I went to Poland to compete, and when I rolled at a BJJ school there, I was caught in a triangle. I was dying to know what that was that neither I nor my master had ever seen.”

Leonid only started seriously practicing the Gracies’ art in 2004, traveling whenever he could, and rolled with multiple teachers known to our readers, like Sergio Benini of GB BH, Alberto Crane and Roger Gracie, until he got his black belt in 2011.

These days, BJJ in the capital Moscow and in the main Russian cities is still not as big as hockey or soccer, but it already boasts promising numbers. There’s talk of 6 to 7 thousand students in the country, mostly children and teenagers.

In 2014 the IBJJF held the first edition of the Moscow Open, with packed stands and competitive divisions, especially at blue and purple belt. For this year, there is the prospect of the first Saint Petersburg Open, with confirmation expected to come soon.

A member of Alliance in Moscow, Ayub Magomadov estimates that there are about 20 Russian black-belts teaching in the country, as well as the many Brazilians that arrive from time to time.

“But it’s not all 20 that compete, so the sport is only beginning,” says the black-belt under Alexandre “Gigi” Paiva. “We are probably four or five who are fighting all the time.”

For those arriving, however, the scene makes a big impression. “The structure of the academies is excellent, and I teach seminars for schools that are always packed, with over a hundred students present,” says three-time world champion Bráulio Estima, who also fought in the last installment of ACBJJ on June 30th in Moscow. “The sport has been growing a lot in the region, not only in Russia but also in Chechnya, Dagestan, the Ukraine, Azerbaijan and other nearby republics.”

Every Brazilian black-belt who visits the country of Oleg Taktarov and Fedor Emelianenko points out the warrior spirit of the Russians, a peculiarity fed by several factors.

“They have an absurd disposition on the mats,” says Bráulio. “First, it’s hard to see a Russian boy who’s never practiced judo, sambo or Olympic wrestling. It’s like finding a kid who’s never played soccer in Brazil. In their culture, every boy must practice a combat sport to gain the respect of the others. Just look at the ears of the general public.”

Bráulio at ACB JJ 14, with champion Lucas Lepri.

Another explanation for the Russians’ tenacity comes from the rules: As pointed out by Graciemag in 2011, most federations of judo and sambo only allow students with medals to change belts — that is, it’s necessary not only to compete, but to win in local tournaments if you want to move up.

In a region of the planet where doing a single-leg is like doing kick-ups in Brazil, it’s hard to tell where Russians will end up when it comes to BJJ. But Bráulio Estima ventures a guess. “They know how to move on the ground since they are little boys, they are explosive when they take down, and they hate to lose. In eight to ten years, who can possibly stop these monsters?”

ACB JJ 14

Moscow, Russia

June 30, 2018

Lucas Lepri def. Davi Ramos, points

João Miyao def. Ary Farias, points

Luiz Panza def. Rodrigo Cavaca, RNC

João Gabriel Rocha def. Nicholas Meregali, points

Igor Silva def. Abdurakhman Bilarov, points

Lucas Hulk def. Romulo Barral, points

Lucas Rocha def. Daud Adaev, armbar

Thiago Sá def. Ayub Magomadov, foot lock

Ali Magomedov def. Bruno Frazatto, foot lock

Gabriel Marangoni def. Osvaldo Queixinho, points

Gabriel Lucas and Marcos Santa Cruz were DQ’d for stalling

Rodnei Barbosa def. Samir Chantre, points

Watch Leonid fighting now-UFC champion Khabib Nurmagomedov:

Khabib Nurmagomedov vs Leonid-Gatovskiy from David Grappler Bista on Vimeo.

The post BJJ in Russia: a panorama of the gentle art in the World Cup’s host country first appeared on Graciemag.